Research reveals that a score of zero, in a 100-point grading scale, is pretty difficult for a student to overcome. For example, if a student gained a zero for not having turned in work, he or she would have to turn in nine assignments, earning 100 points each, to overcome the impact of that zero score.

Research reveals that a score of zero, in a 100-point grading scale, is pretty difficult for a student to overcome. For example, if a student gained a zero for not having turned in work, he or she would have to turn in nine assignments, earning 100 points each, to overcome the impact of that zero score.

Many teachers just excuse the task, rather than assigning a zero for no work done. But this suggests that the tasks themselves are not valuable, and that the student should not have a grade that represents their learning.

To avoid the zero mark, teachers should take another approach: providing an additional opportunity for students to show their work.

#nozeros

To act on these ideas, I started a lunch routine called #nozeros. (The name came from a kid’s suggestion for a classroom assignment, and it helped to entice the kids to the event.)

Here’s how it works. When students don’t turn in an assignment in class like a monthly reading log, I give them a lunch pass with #nozeros written on it. This requires them to spend a lunch in my classroom.

At first, students came reluctantly when they were given these passes. They expected a punishment-type lunch with the teacher.

Instead, they came and realized that I just wanted to give them a score on their work, and that I would help them if they liked. They could also work alone if they prefered.

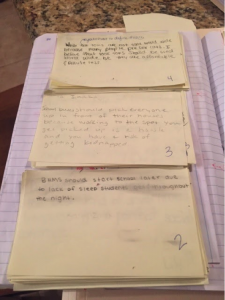

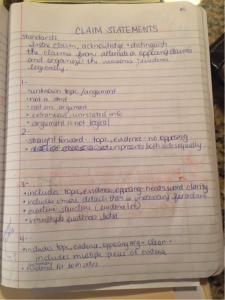

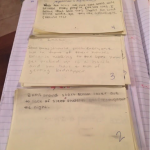

If, for example, the missed assignment is a reading log, students write a claim about something that happened in their book. This task shows me that students have read the book, and it takes about a minute to complete. Students can leave when they finish, though some choose to stay and hang out.

These lunches have become something fun, and as my husband, a self-described average student, observes, “It’s not that they don’t want to do the assignment or can’t do the assignment. It’s that they forgot at night or don’t want to do it at home. They love this option because it gets their work in.” For me, the lunches make sense because I get work and students get a viable alternative to show that work.

Now, I have no zeros in my grade book and a lunch routine of openness and growth with my students.

The Growth Mindset

This kind of routine is part of my conscious effort at establishing a growth mindset in my classroom. I want students to realize that they can do their best work—and that sometimes this takes multiple attempts.

To help establish the growth mindset in my classroom this year, I also started modeling the work for my current students, and modeling work at all levels of achievement. All of my students’ work can be revised and resubmitted for feedback.

In addition to the #nozeros meetings, I opened my classroom at lunch time to offer kids one-on-one help if they desired.

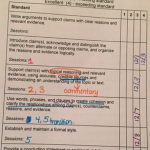

One student, Matt, became a weekly participant, with a goal to increase his level of achievement on our weekly narrative writing piece. At these lunch sessions, we worked to increase the elaboration in his weekly story, and to grow his craft in areas like character creation, dialogue, passive voice, and modified structure. My descriptive feedback, which connected directly to his writing, allowed Matt to be successful.

As we continued to work on the assignment in class, I would gently encourage him to name the skills we worked on at lunch, and remind him to make use of them.

After several weeks, Matt, smiling, announced that he got a 4 (a mark of excellent achievement)—because he worked to get it. He wasn’t bragging, though, when he said this to our class. He was encouraging others to put in some work to grow their achievement. I smiled.

From these experiences, I’ve learned a few things as a teacher:

- Students are honest evaluators of their own work.

- Students will strive to meet expectations you set when they trust that you care about them and their work.

- Student can gain confidence through achievement on meaningful tasks.

It’s important to allow kids to do their best, even when the methods to achieve this may look different.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.

For the next two years, I will be part of the

For the next two years, I will be part of the

At the start of school, I had a plan for connecting to the students in my classes. I would start by connecting on a personal level, so that they would be open to growing as readers and writers on a professional level.

At the start of school, I had a plan for connecting to the students in my classes. I would start by connecting on a personal level, so that they would be open to growing as readers and writers on a professional level. realized that I was as willing to help with their work as I was to greet each of them at the door.

realized that I was as willing to help with their work as I was to greet each of them at the door. At the end of the year, teachers must officially reflect on their teaching and the impact that it had on kids. Now, this is not to say that teachers don’t reflect throughout the year and observe the impact they have on their students, but it is hard to avoid this question at the end of the year. So, I took out my neatly labeled evaluation folder and looked at my goals. My district requires that I write 3 goals that align with curriculum standards, but also with our district goals. We write these in the SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, timely) goal format. While, I’m a methodical and organized person, I realized quickly that my projected outcomes turned out very differently than I expected. Additionally, my actual student outcomes produced additional questions I need to consider.

At the end of the year, teachers must officially reflect on their teaching and the impact that it had on kids. Now, this is not to say that teachers don’t reflect throughout the year and observe the impact they have on their students, but it is hard to avoid this question at the end of the year. So, I took out my neatly labeled evaluation folder and looked at my goals. My district requires that I write 3 goals that align with curriculum standards, but also with our district goals. We write these in the SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, timely) goal format. While, I’m a methodical and organized person, I realized quickly that my projected outcomes turned out very differently than I expected. Additionally, my actual student outcomes produced additional questions I need to consider. Still, this brings up an issue I’m still pondering: I believe that in order to consider work truly digital it must be transformed technology–not able to be created without technology. Clearly, we were already doing this notebook work before technology, so how did this digital version help to accomplish my goal? My students and I quickly realized that styluses leave many things to be desired, and we knew that simply putting this work in an online notebook versus a regular notebook wasn’t enhancing the writing process so much. So, I was on my way to creating a digital reading/writing notebook as my goal stated, but at this point, I had to alter the the attainable part of this goal.

Still, this brings up an issue I’m still pondering: I believe that in order to consider work truly digital it must be transformed technology–not able to be created without technology. Clearly, we were already doing this notebook work before technology, so how did this digital version help to accomplish my goal? My students and I quickly realized that styluses leave many things to be desired, and we knew that simply putting this work in an online notebook versus a regular notebook wasn’t enhancing the writing process so much. So, I was on my way to creating a digital reading/writing notebook as my goal stated, but at this point, I had to alter the the attainable part of this goal. Then, I found myself with a day of digital mishaps that opened the opportunity for students to choose how they organized and crafted their work. I punted quickly with paper copies of the work or the choice for students to create their own page of notes and examples rather than using my digital versions. Students made their choices, and we moved forward with learning for the day. The next day, with all technology working, a student inquired if I had any paper copies like yesterday. This simple question gave me pause. I was embarrassed. I used to be so proud of the choices I provided the students in my classroom, and even more proud when they found their niche and created something that was special to them. I also used to cherish the beauty and variety that students brought to their notebooks – they had my lesson labels and tape-in notes, but they had doodles that added beauty to their pages and colors that shone through the typed notes, as well as messy, but purposeful writing. Now, the beautiful handwriting scripts are gone as are the doodles in the page margins. Their work is still unique in their content and their work is still special to who they are as writers, but it looks very uniform. When I paused, I realized that I also missed my colorful handwritten pages and the little anecdotes from kids that I would add. I got so caught up in using the technology because it was my goal that I forgot about being the teacher that I was.

Then, I found myself with a day of digital mishaps that opened the opportunity for students to choose how they organized and crafted their work. I punted quickly with paper copies of the work or the choice for students to create their own page of notes and examples rather than using my digital versions. Students made their choices, and we moved forward with learning for the day. The next day, with all technology working, a student inquired if I had any paper copies like yesterday. This simple question gave me pause. I was embarrassed. I used to be so proud of the choices I provided the students in my classroom, and even more proud when they found their niche and created something that was special to them. I also used to cherish the beauty and variety that students brought to their notebooks – they had my lesson labels and tape-in notes, but they had doodles that added beauty to their pages and colors that shone through the typed notes, as well as messy, but purposeful writing. Now, the beautiful handwriting scripts are gone as are the doodles in the page margins. Their work is still unique in their content and their work is still special to who they are as writers, but it looks very uniform. When I paused, I realized that I also missed my colorful handwritten pages and the little anecdotes from kids that I would add. I got so caught up in using the technology because it was my goal that I forgot about being the teacher that I was.  As I reflect at the end of the year, I recall what a mentor said to me–that with older students like mine, I could let them choose. She suggested a short research project where kids choose a way to do their writing work as I offer them options and teach about how writing in different genres requires different tools. I know now that my projected outcomes differed from my goal statements because we had to find the right tools for our needs. While I did accomplish my goal – incorporating a digital reading/writing notebook into students’ practice, I am left with my second question: what is a workshop teacher to do without paper notebooks? And I am still thinking about how digital work can enhance the reading/writing workshop in my classroom.

As I reflect at the end of the year, I recall what a mentor said to me–that with older students like mine, I could let them choose. She suggested a short research project where kids choose a way to do their writing work as I offer them options and teach about how writing in different genres requires different tools. I know now that my projected outcomes differed from my goal statements because we had to find the right tools for our needs. While I did accomplish my goal – incorporating a digital reading/writing notebook into students’ practice, I am left with my second question: what is a workshop teacher to do without paper notebooks? And I am still thinking about how digital work can enhance the reading/writing workshop in my classroom. Several years ago, I developed an inquiry question that asked if students use the language of workshop. Because I consistently use the “ELA Speak” of mentor texts, seed ideas, and generating strategies, I questioned, do students know these terms and use them to forge work?

Several years ago, I developed an inquiry question that asked if students use the language of workshop. Because I consistently use the “ELA Speak” of mentor texts, seed ideas, and generating strategies, I questioned, do students know these terms and use them to forge work?

This tool is exclusively available for Google Education users and manages class lists and links to student’s Google Drive accounts.

This tool is exclusively available for Google Education users and manages class lists and links to student’s Google Drive accounts. This platform houses online documents that can be created, shared, and collaborated on.

This platform houses online documents that can be created, shared, and collaborated on. This program’s purpose is online organization and notebook creation. Penultimate is an Evernote sister app which syncs data but also allows handwritten notes.

This program’s purpose is online organization and notebook creation. Penultimate is an Evernote sister app which syncs data but also allows handwritten notes.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the