Technology has certainly exploded between the time I started preparing to become a teacher and now, but lately I’ve been thinking about Google–and the ways that education can, and should, mirror the company’s ubiquitous technology.

Technology has certainly exploded between the time I started preparing to become a teacher and now, but lately I’ve been thinking about Google–and the ways that education can, and should, mirror the company’s ubiquitous technology.

We don’t need to focus on memorization.

We have to confront our fascination with facts and memorization: Why bother if you can Google it? In the age of information overload, we’re finding that it’s far more important to teach our students how to analyze multiple sources, determine credibility, and read around a topic to gain a deeper understanding of it.

That’s true for vocabulary, too. Vocabulary in English classes used to consist mostly of looking up definitions in dusty dictionaries and, if your teacher was really on top of things, using the word in a few different sentences or drawing a picture of it. Now, the standards call for students to flexibly use a variety of strategies to determine meaning when they encounter unfamiliar vocabulary; the last strategy involves looking it up in reference materials (ahem, Googling it).

Let’s prepare our students to collaborate.

There is inherent value in teaching the collaborative skills that will prepare our students for success beyond their high school walls. We design projects and lessons so that students will bounce ideas back and forth, develop questions, and seek answers together.

In many ways, this mirrors the Google Drive platform. On Google Drive, you don’t just create documents inside your own software, then print or attach to share. Instead, you have control over how and with whom you share your folders as you’re working. Sure, you can still choose to keep something private and then share it only once you’re ready for the work to get into others’ hands. But now we have the opportunity to collaborate on our work as we’re drafting–in real time–and it’s changing the face of how we work.

It’s been less than a year since I fully switched over to Google as my primary mode of doc creation, but I already have a hard time imagining drafting something without hitting that little comment button to get feedback from my colleagues.

Tech companies update their software. We should update our practices.

We all know that feeling when our favorite technology company updates something. It’s almost like we go through Kubler-Ross’ seven stages of grief each time our tech changes. But the thing is, we do reach acceptance and adapt to the changes–and we do it quickly.

Part of this has to do with semantics. Google has been telling its users about some upcoming changes to its Drive services and apps. But they aren’t just adapting, changing, or revising: they’re upgrading.

I hear teachers say all the time that “X worked for me when I was in school…” If I applied that logic to my tech life, I’d have to accept being completely okay with only a house phone and a dial-up internet connection. Isn’t it only fair to our students that we upgrade our teaching like we upgrade our technology?

Employees in the tech industry feel valued. Shouldn’t teachers?

I’ve never been to Google’s headquarters myself, and I’m sure there’s more than meets the eye, but still: the company ranks at the top of employee satisfaction surveys year after year. In an interview with Fast Company, Karen May, Google’s VP of people development, explains that the company believes that focusing on their employees’ health and happiness is what ultimately determines their success.

I think we are all realists and know that our funding sources are vastly different from Google’s, so I don’t think too many teachers expect field trips to exotic locales. But in our current climate, I think we’d do well to take a step back and think about how we can support the health and happiness of our teachers, our administrators, and ultimately, our students.

Megan Kortlandt (@megankortlandt) is a secondary ELA consultant and reading specialist for the Waterford School District. In the mornings, she teaches at Durant High School, and in the afternoons, she works with all of Waterford’s middle and high school teachers and students through the Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment department. Every time Megan goes grocery shopping, her cart makes her appear to be exceptionally healthy, but don’t be fooled. The healthy stuff is all for her pet rabbit, Hans.

Megan Kortlandt (@megankortlandt) is a secondary ELA consultant and reading specialist for the Waterford School District. In the mornings, she teaches at Durant High School, and in the afternoons, she works with all of Waterford’s middle and high school teachers and students through the Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment department. Every time Megan goes grocery shopping, her cart makes her appear to be exceptionally healthy, but don’t be fooled. The healthy stuff is all for her pet rabbit, Hans.

‘Tis the season . . . for professional learning! Conferences, early releases, and late-start days; inspiring speakers, intense conversations–and then we return back to our students and apply the lessons. It’s one last big push to propel us to the end of the school year.

‘Tis the season . . . for professional learning! Conferences, early releases, and late-start days; inspiring speakers, intense conversations–and then we return back to our students and apply the lessons. It’s one last big push to propel us to the end of the school year. Consolidating big ideas and notes into a Google Doc. Learners’ block! We were paralyzed and couldn’t decide what was important to tackle first. We agreed to wait a week and then to revisit our notes. Additionally, mid-year reassessments were in full swing. And so with data in hand, it was much easier to focus and prioritize what to put into action. This also meant we would have to let some things go for now.

Consolidating big ideas and notes into a Google Doc. Learners’ block! We were paralyzed and couldn’t decide what was important to tackle first. We agreed to wait a week and then to revisit our notes. Additionally, mid-year reassessments were in full swing. And so with data in hand, it was much easier to focus and prioritize what to put into action. This also meant we would have to let some things go for now. Lynn Mangold Newmyer has been an educator for 42 years. She is a Reading Recovery Teacher Leader and an Elementary Literacy Coach in the Walled Lake Consolidated School district. Lynn has presented at state, national, and international conferences and has taught graduate classes at Oakland University. She currently teaches her students at Loon Lake Elementary. Lynn emphatically believes that you can never own too many picture books. You can follow her on Twitter at

Lynn Mangold Newmyer has been an educator for 42 years. She is a Reading Recovery Teacher Leader and an Elementary Literacy Coach in the Walled Lake Consolidated School district. Lynn has presented at state, national, and international conferences and has taught graduate classes at Oakland University. She currently teaches her students at Loon Lake Elementary. Lynn emphatically believes that you can never own too many picture books. You can follow her on Twitter at  “Hattie. Take a look at this. One of your kids wrote this, and I don’t know what to do with it.”

“Hattie. Take a look at this. One of your kids wrote this, and I don’t know what to do with it.” So our first step was a tiny one. Brian’s kids wrote some essays, and he dropped the students off to my classes, where they received some feedback about focus and organization. It was a great experience for my students to practice giving constructive feedback, and Brian was happy with the help his kids received.

So our first step was a tiny one. Brian’s kids wrote some essays, and he dropped the students off to my classes, where they received some feedback about focus and organization. It was a great experience for my students to practice giving constructive feedback, and Brian was happy with the help his kids received.

At the start of December, I attended a workshop at the Detroit Port Authority Lofts, which, it turns out, is an event space, not a place where ships check in. I’ve lived in southeast Michigan my entire life, and spent many, many hours in the city. But I didn’t know this place was there. I thought, The city of Detroit is like teachers: there’s so much good stuff happening, but no one knows about it, or the ones who do know treat the information like it’s secret.

At the start of December, I attended a workshop at the Detroit Port Authority Lofts, which, it turns out, is an event space, not a place where ships check in. I’ve lived in southeast Michigan my entire life, and spent many, many hours in the city. But I didn’t know this place was there. I thought, The city of Detroit is like teachers: there’s so much good stuff happening, but no one knows about it, or the ones who do know treat the information like it’s secret.

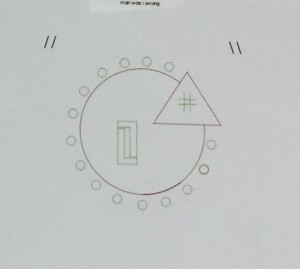

were learning about conics. With that, they created logos for us to vote on. Most of my department picked the logo shown on the right. It reflected our desire to have a design that opened a conversation, by provoking a person to ask about the logo. The shapes are meant to represent aspects of our discipline and practice. We didn’t want books or pens or apples. Too

were learning about conics. With that, they created logos for us to vote on. Most of my department picked the logo shown on the right. It reflected our desire to have a design that opened a conversation, by provoking a person to ask about the logo. The shapes are meant to represent aspects of our discipline and practice. We didn’t want books or pens or apples. Too  Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a