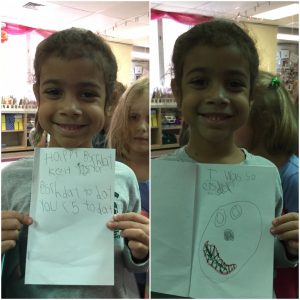

My daughter is writing a great story about the poop emoji plunger she won at our family white elephant party at Christmas.

It’s a great tale of intrigue and strategy. And even though she’s only in kindergarten, she’s already learning that her writing is powerful. In this case, she can use it to make people laugh–and that’s one of her highest priorities these days.

This makes me think about Ralph Fletcher’s Joy Write, a book that’s intended for K-6 teachers, but which has valuable lessons for the upper grades too. Fletcher’s book looks at the ways in which teachers can make writing a joyful experience for students. In the opening chapter, for instance, he compares writing workshop to a hot-air balloon: “For roughly an hour each day the kids would climb in and–whoosh!–up they’d go.”

But how do you create joy when, as in my AP class, there’s a pretty high-stakes test looming?

Let students choose their own topics.

My students have to be prepared to write three very specific types of essays by May. It would be irresponsible to not prepare them to do that.

But I don’t have to dictate their topics.

Why not analyze a song, a TV show, or even a threaded Twitter rant they come across? Write an op-ed on something about which they’re passionate? Research topics of their choosing?

My students won’t necessarily have the same amount of freedom my daughter, Molly, has in kindergarten. But there’s room for a lot of joy if I commit to conferencing with each student and helping each one find ways to connect to their writing topics.

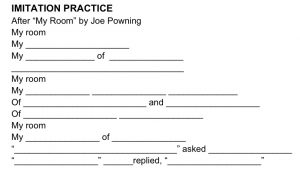

Give students an opportunity to write playfully.

Just as it would be irresponsible to not prepare them to write those three types of essays, I’m beginning to think it’s irresponsible to not give them chances to do other types of writing as well.

Fletcher argues in his book that “writing workshop has become more restrictive . . . less free-flowing, less student centered” and he’s right. He suggests creating a greenbelt that preserves space for “raw, unmanicured, uncurated” writing.

I love this idea, and I think I can make space for a greenbelt in my room, too. Why not dedicate a little time each day to some free, “unmanicured” writing? It will be tough at first; my students have not had many opportunities in recent years to write playfully. But I think if I stick with it, they’ll get there. I might start by just sharing Molly’s poop-emoji-plunger tale and see what that inspires with them.

There’s not enough time for everything, so let some things go.

It’s time consuming to conference with individual students, helping them to find topics. Greenbelt writing eats up class time.

So I have to let stuff go.

When I started teaching AP Language years ago, we examined six or seven really dense essays as a class each unit. Was it important for their critical reading? Sure. But is it more important than digging into a topic they love? More important than feeling the joy of knowing you’ve crafted a sentence that is finally, exactly, what you want?

I don’t think it is. I think whooshing takes time. I think if I want my students to find some joy in their writing, I have to accept that it’ll be a messy process that will happen on a different timeline for each student. Nobody gets anywhere fast in a hot air balloon, but it’s sure beautiful once it’s in the air.

Hattie Maguire (@teacherhattie) hit a milestone in her career this year: she realized she’s been teaching longer than her students have been alive (17 years!). She is spending that 17th year at Novi High School, teaching AP English Language and AP Seminar for half of her day, and spending the other half working as an MTSS literacy student support coach. When she’s not at school, she spends her time trying to wrangle the special people in her life: her 8-year-old son, who recently channeled Ponyboy in his school picture by rolling up his sleeves and flexing; her 5-year-old daughter, who has discovered the word apparently and uses it to provide biting commentary on the world around her; and her 40-year-old husband, whom she holds responsible for the other two.

Hattie Maguire (@teacherhattie) hit a milestone in her career this year: she realized she’s been teaching longer than her students have been alive (17 years!). She is spending that 17th year at Novi High School, teaching AP English Language and AP Seminar for half of her day, and spending the other half working as an MTSS literacy student support coach. When she’s not at school, she spends her time trying to wrangle the special people in her life: her 8-year-old son, who recently channeled Ponyboy in his school picture by rolling up his sleeves and flexing; her 5-year-old daughter, who has discovered the word apparently and uses it to provide biting commentary on the world around her; and her 40-year-old husband, whom she holds responsible for the other two.

Rick Kreinbring (

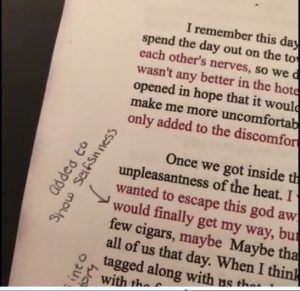

Rick Kreinbring ( Writing instruction has become my favorite part of teaching, though it didn’t always come easily. In the beginning, my own writing was stilted in structure and lacked voice. I wrote what I had been taught, which was a five paragraph essay and a five sentence paragraph. Not only was my writing boring. The moves I made to create it were not defined enough for students to use as models, except for stilted, formulaic writing that also lacked voice and a sense of ownership.

Writing instruction has become my favorite part of teaching, though it didn’t always come easily. In the beginning, my own writing was stilted in structure and lacked voice. I wrote what I had been taught, which was a five paragraph essay and a five sentence paragraph. Not only was my writing boring. The moves I made to create it were not defined enough for students to use as models, except for stilted, formulaic writing that also lacked voice and a sense of ownership. Amy Gurney (

Amy Gurney ( My last post was about the new app

My last post was about the new app

Bear’s Loose Tooth

Bear’s Loose Tooth Tricia Ziegler (Twitter:

Tricia Ziegler (Twitter:  So it’s November, and it may seem odd to see the title “early choice” in a blog post. It’s not early in the year, and yet for an elementary teacher whose students are blogging, it is.

So it’s November, and it may seem odd to see the title “early choice” in a blog post. It’s not early in the year, and yet for an elementary teacher whose students are blogging, it is. Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for

Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for

Caroline Thompson (

Caroline Thompson (

Rick Joseph (

Rick Joseph ( It’s that time of year here in Michigan: the dreaded standardized testing window we now call M-STEP. My 5th graders just endured five days of this testing over a two-week period. The first two days were ELA tests–hours of online reading and writing. Needless to say, after the second afternoon my kiddos were in need of a break.

It’s that time of year here in Michigan: the dreaded standardized testing window we now call M-STEP. My 5th graders just endured five days of this testing over a two-week period. The first two days were ELA tests–hours of online reading and writing. Needless to say, after the second afternoon my kiddos were in need of a break. This day really got me thinking about workshop and curriculum. We power through what we need to teach: mini lessons, teaching points, big ideas. We give kids lots of independent practice within the unit we are teaching.

This day really got me thinking about workshop and curriculum. We power through what we need to teach: mini lessons, teaching points, big ideas. We give kids lots of independent practice within the unit we are teaching.