My last post was about the new app Flipgrid and my plan to use it to get my students talking about revision. My goal was pretty simple: Get students to make meaningful revisions that they could explain and support as good writing.

My last post was about the new app Flipgrid and my plan to use it to get my students talking about revision. My goal was pretty simple: Get students to make meaningful revisions that they could explain and support as good writing.

In order for students to perform well on this revision assignment, they needed to succeed in two separate phases. First, they had to make revisions–based on very directed feedback from me–that improved a section of their paper. Then, they had to fill 90 seconds of video with their explanation of why their revisions constituted effective writing.

Here’s what my rubric looked like for the video itself. In order to receive full credit:

The video

- clearly explains specific and meaningful changes to the text

- outlines why the changes were made, using the language of the rubric strand

- includes visible and thorough annotation of the revised section to help guide viewers

- Clearly demonstrates that the author understands how to improve writing for future pieces

- feels polished and uses the full 90 seconds available

When I finalized that rubric, I had to tell myself that if worse came to worst, I could always toss the scores and tell the kids it was a learning experience. I had faith in them, but this assignment basically demanded that each of my writers speak for a minute and a half…like a professional writer.

Which is why I’m pretty comfortable saying that Flipgrid is a game changer. I’m going to let the students’ efforts speak for themselves, but first some context: they revised a narrative that reimagined a scene from The Great Gatsby from a different character’s perspective. My feedback on it narrowed them in on certain areas of their writing that they might choose to improve on (narrator’s voice, organization, etc.), and then they chose one of those for the video. (If you’d like to skip ahead and watch the videos, scroll down to the bottom of this post.)

Flippin’ Fantastic

Turns out my concerns about their meeting the rubric demands were misguided. Most of them killed it with this assignment.

Take note of a few heartening examples:

- A student who exited ESL about a year ago added sensory detail describing a character praying on the “cold, painful floor.” His explanation of the revision: “This emphasized that he was really sad and was begging for God’s help.”

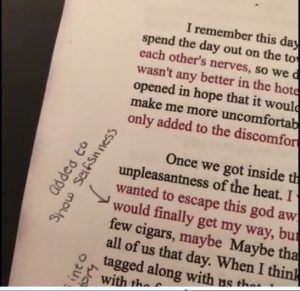

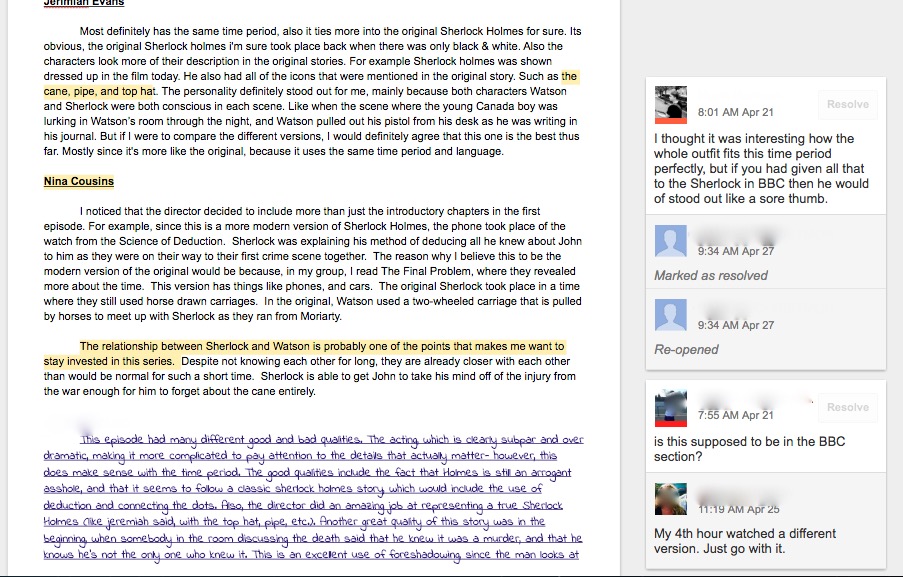

- One of my more talented writers, whose original narrative was imbalanced with long flashbacks, color coded her revision to emphasize how her new organizational structure improved things: “There’s an obvious balance [now] between what’s going on in the scene and what Daisy is thinking about,” she explained while pointing to the modified paragraph order.

A frame from a student video: note the color coding and annotation of how she developed narrative voice.

- A writer who had struggled to establish the voice of her narrator added several lines of narrative reflection to establish her main character’s selfish motivations in the scene, and explained how this transformed the narrative perspective.

- A writer who enjoys playing with diction added the phrase “riled me up” to her narrator’s reflections and explained, simply, “I thought that was cool.”

It was cool. All of it was cool. Even the kids whose revisions themselves weren’t quite masterful were able to articulate not only what they had improved in their writing but also why it was better.

Re-vid-sion Is Key

If you like what you’re seeing but you’re also wondering whether the video element really matters to its success, think about this: Talking about writing is a stressful endeavor for most young writers–even the good ones. Using Flipgrid to turn that process into a student-driven, premeditated, predictable, finite process alleviates all sorts of stresses that otherwise tend to silence less experienced writers.

Video is a familiar medium that allows them to combine a visual outline of their efforts with a verbal elaboration of their reasoning. As a result, many of my students suddenly loosened up a bit and actually had some fun talking about their writing (seriously–one student even took a picture of himself with a wad of dollar bills in his mouth as the opening to his video, which I’m going to just presume is a reference to all the wealth in The Great Gatsby and try not to think about ever again).

There’s one more treasure buried in this sea of video footage. My students’ grid of videos are my new models for future writing. Don’t know how to structure dialogue? Go watch Ken’s video. Did I knock your organization last time around? Check out what Lauren did with her opening paragraphs on that last assignment.

It’s the most productive 90 seconds my kids have ever spent on their phones.

The Videos

Here’s a small selection of student videos:

Michael Ziegler (@ZigThinks) is a Content Area Leader and teacher at Novi High School. This is his 15th year in the classroom. He teaches 11th Grade English and IB Theory of Knowledge. He also coaches JV Girls Soccer and has spent time as a Creative Writing Club sponsor, Poetry Slam team coach, AdvancEd Chair, and Boys JV Soccer Coach. He did his undergraduate work at the University of Michigan, majoring in English, and earned his Masters in Administration from Michigan State University.

In the beginning of our blogging year, I always tell students to wait to comment on each other’s writing. There are always those who ignore me and add all sorts of silly comments with emojis. What they don’t realize is that I have to approve all comments first. I control this intentionally because I want to teach them how to comment.

In the beginning of our blogging year, I always tell students to wait to comment on each other’s writing. There are always those who ignore me and add all sorts of silly comments with emojis. What they don’t realize is that I have to approve all comments first. I control this intentionally because I want to teach them how to comment. Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for

Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for  So it’s November, and it may seem odd to see the title “early choice” in a blog post. It’s not early in the year, and yet for an elementary teacher whose students are blogging, it is.

So it’s November, and it may seem odd to see the title “early choice” in a blog post. It’s not early in the year, and yet for an elementary teacher whose students are blogging, it is. In May, as the school year was winding down, I was met with an all-too-common challenge: running out of time. There were about four weeks left, and the calendar was quickly filling with standardized tests, field trips, and sports competitions. I needed two solid weeks of writing workshops with my tenth graders to complete their final writing piece–an op-ed–but it looked like ten kids would be gone each day for the next four weeks.

In May, as the school year was winding down, I was met with an all-too-common challenge: running out of time. There were about four weeks left, and the calendar was quickly filling with standardized tests, field trips, and sports competitions. I needed two solid weeks of writing workshops with my tenth graders to complete their final writing piece–an op-ed–but it looked like ten kids would be gone each day for the next four weeks.

Hattie Maguire (

Hattie Maguire (

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a

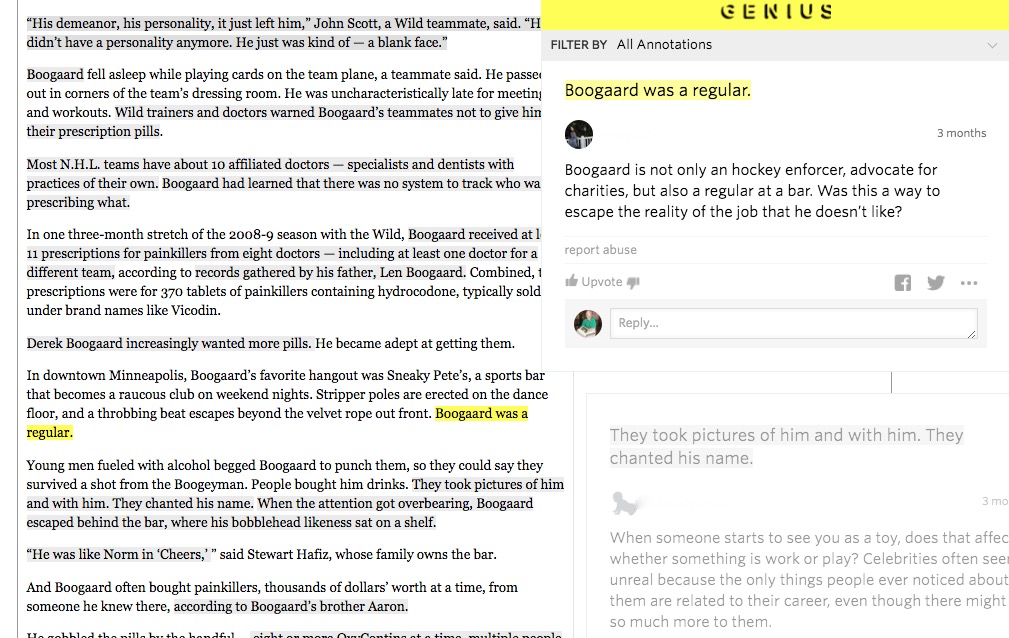

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a  As a workshop-model Language Arts teacher, I am always searching for excellent mentor texts to guide students’ writing and reading. The hardest mentor texts to find are informational texts that are grade-level appropriate, as well as high interest in content.

As a workshop-model Language Arts teacher, I am always searching for excellent mentor texts to guide students’ writing and reading. The hardest mentor texts to find are informational texts that are grade-level appropriate, as well as high interest in content.  Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the

Dr. Troy Hicks

Dr. Troy Hicks