Full disclosure: I’ve never thought of myself as a poetry person. I taught a lot of Debate for the first half of my career and then I shifted into AP Language and Composition. I’m argument, research, rhetoric. Not poetry.

It’s not that I dislike poetry–I loved studying it in high school and college–but the way I studied it has never meshed with the curriculum I teach.

In the past few years, however, I’ve found poems popping up at just the right moment, providing exactly the messages or skill lessons my students need.

Here are five ways I sneak poetry into a rhetoric class:

A Way to Begin Tough Conversations

Though I sometimes avoided hot topics as a young teacher, there is little today that I’m unwilling to discuss with my students. Still, I try very hard to reign in my own opinions because whether I like it or not, many students see me as the person who holds the position of power in the room. What I share with the class shows what I value, and I must be careful how I use my voice.

For me, poems are often a good starting point because their arguments are less explicit than those you would find in an op-ed. Recently, my students read and responded to the poem “Playground Elegy,” by Clint Smith. The poem makes an argument, but it also gives students a way into the discussion that is less intimidating–relatable imagery of a common childhood experience. In my class, this shared imagery gave them some common ground to begin a discussion about race and violence.

A Way to Examine Writers’ Choices

Poetry also provides quick mentor texts for discussing a writer’s choices. In September, George Clooney wrote a poem about the take-a-knee movement. The poem is a simple one, but provided a quick study in analysis. Why a poem? Why repeat the word “pray”? What’s the impact of the final line?

We could accomplish a lot analytically in ten minutes. A longer piece might have taken the whole hour to wade through. Again, there was an argument, too. After our analysis of the discussion, we were able to shift naturally into a discussion of the argument Clooney was making.

A Way to Process Big Emotions

Sometimes poems aren’t for arguing or analyzing, though. The day after the Parkland shooting, I knew I needed to address it with my students. Tricia Ebarvia of the Moving Writers blog encouraged me to just write with my students, and suggested several poems as a prompt. We ended up writing in response to “The Way It Is” by William Stafford and my students considered what it means to hold onto a thread and keep going when things are difficult. The notebook writing they did that day helped them process a lot of emotions and fears that they hadn’t had a chance to work through.

A Way to Spark Research Questions

In addition to argumentation, my students also do a lot of research. Poems can serve as perfect sparks for research questions because they often leave things unanswered. Students are used to having research topics, but when they have research questions, I find their thinking, researching, and writing becomes much more complex.

For example, after reading “Gate A4,” by Naomi Shihab Nye, and “Broken English,” by Rupi Kaur, students had all kinds of questions about the extent to which language impacts our daily lives and the way we interact with one another. Had I just asked them to research, for example, whether or not the United States should have a national language, many would have never examined the murkier, more complex areas of the topic.

A Way to Blow Off Steam

Last week, following the SAT test, my juniors were burned out. I shared a funny tweet I’d seen riffing on the William Carlos Williams poem “This is Just to Say” and explained how that had become a meme. To give our brains a break, we wrote our own poems. Though I had only intended to give their brains a little break, this, too, turned into an easy (and fun!) lesson about a writer’s choices. What’s the impact of that giant long line? What was the writer trying to accomplish and why is it successful?

In the introduction to her book Poems Are Teachers, Amy Ludwig Vanderwater explains that “poems wake us up, keep us company, remind us that our world is big and small. And, too, poems teach us to write. Anything.” Regardless of the course you teach, there is a space for poetry. I’ve found lots of spaces in my course and I’d argue (see? It’s my thing) that you can, too.

Hattie Maguire (@teacherhattie) hit a milestone in her career this year: she realized she’s been teaching longer than her students have been alive (17 years!). She is spending that 17th year at Novi High School, teaching AP English Language and AP Seminar for half of her day, and spending the other half working as an MTSS literacy student support coach. When she’s not at school, she spends her time trying to wrangle the special people in her life: her 8-year-old son, who recently channeled Ponyboy in his school picture by rolling up his sleeves and flexing; her 5-year-old daughter, who has discovered the word apparently and uses it to provide biting commentary on the world around her; and her 40-year-old husband, whom she holds responsible for the other two.

Hattie Maguire (@teacherhattie) hit a milestone in her career this year: she realized she’s been teaching longer than her students have been alive (17 years!). She is spending that 17th year at Novi High School, teaching AP English Language and AP Seminar for half of her day, and spending the other half working as an MTSS literacy student support coach. When she’s not at school, she spends her time trying to wrangle the special people in her life: her 8-year-old son, who recently channeled Ponyboy in his school picture by rolling up his sleeves and flexing; her 5-year-old daughter, who has discovered the word apparently and uses it to provide biting commentary on the world around her; and her 40-year-old husband, whom she holds responsible for the other two.

As my students work through the

As my students work through the  Not all the conversations go this way. But enough of them do that I take notice. Is my thinking about empathy and how to get it wrong? I’m also worried that some of these students will slip back into “a prove my point/win the argument” mindset, but I am encouraged.

Not all the conversations go this way. But enough of them do that I take notice. Is my thinking about empathy and how to get it wrong? I’m also worried that some of these students will slip back into “a prove my point/win the argument” mindset, but I am encouraged. Rick Kreinbring (

Rick Kreinbring ( “There are no more words left in me to write, I think.” (R

“There are no more words left in me to write, I think.” (R

Hattie Maguire (

Hattie Maguire ( Yes, we have to do a research project in kindergarten!

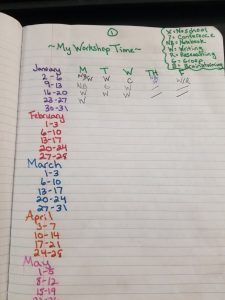

Yes, we have to do a research project in kindergarten! We also looked for kid-appropriate videos and zoos that had viewing cameras on the animals. The San Diego Zoo, for example,

We also looked for kid-appropriate videos and zoos that had viewing cameras on the animals. The San Diego Zoo, for example,  Tricia Ziegler (Twitter:

Tricia Ziegler (Twitter:

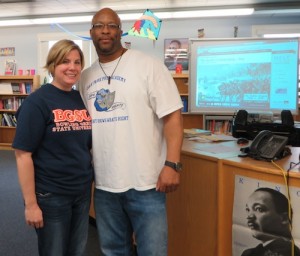

This experience showed me and Doug that it is imperative for disciplines to collaborate. Neither of us could have gotten the quality of work the students produced had we done this separately. For the first time, students were seeing exactly how the skills they learn in their individual classes apply to all classes. They were developing skills–research skills, presentation skills– not just memorizing facts and figures.

This experience showed me and Doug that it is imperative for disciplines to collaborate. Neither of us could have gotten the quality of work the students produced had we done this separately. For the first time, students were seeing exactly how the skills they learn in their individual classes apply to all classes. They were developing skills–research skills, presentation skills– not just memorizing facts and figures. Lisa Kraiza teachers eighth grade English Language Arts at Oak Park Preparatory Academy. She is also a member of the Core Leadership Team of the

Lisa Kraiza teachers eighth grade English Language Arts at Oak Park Preparatory Academy. She is also a member of the Core Leadership Team of the