As a teacher who works with struggling readers, my favorite time of year is the end of the semester. It’s then that I assess students’ progress. When I give them their results, some can’t believe it. Some want to call their parents to share the good news. And some even cry. They all beam with pride.

As a teacher who works with struggling readers, my favorite time of year is the end of the semester. It’s then that I assess students’ progress. When I give them their results, some can’t believe it. Some want to call their parents to share the good news. And some even cry. They all beam with pride.

What’s not to love?

The time of year that is a close second, though, is the just-past-halfway-point. Yes, I know that this is when students and teachers tend to count down toward the next break, with nothing but survival on their minds. But in the Adolescent Accelerated Reading Initiative, or AARI, things are starting to get exciting.

AARI is a program that quickly brings struggling students up to grade level, using a variety of research-supported techniques. During the first few weeks of AARI, we learn a lot about an author’s purpose. We also learn how authors achieve their purposes through the organization of their texts. We focus heavily on text structures and “mapping” a text’s organization, which shows the relationships between facts and information.

It’s at this point in the year, this just-past-halfway-point, when my students start to recognize text structures in their books—on their own. I love this because it shows me that they’re ready for more. They’re ready to start transitioning to grade-level texts.

The Real-World Connection

There are other signs that they’re ready. Sometimes a student will burst into the room at the beginning of the period and exclaim, “You’ll never believe what we’re doing in Chemistry! The teacher gave us a chart, and he didn’t even realize it was a matrix!”

Seeing kids make these connections to their learning is what makes my work so vital. It’s why even as I’m launching the first weeks of the class, my focus is always on my endpoint: helping students use their intervention in relevant, real-world applications.

This real-world focus starts early. Toward the beginning of the semester, we start talking about our text structures in the “real world.” I start this discussion by asking students what clues readers have in other, more difficult texts.

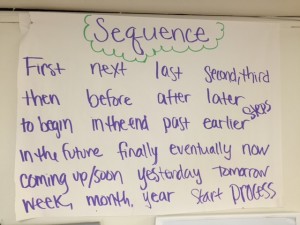

Together, we make anchor charts of “clue” words and phrases that writers use to signal that they are using a particular text structure to organize their thoughts. We post these in the room and add to them as we encounter more. Having these word banks arms students with tools to start recognizing text structures when the texts aren’t so easy.

Starting Small

Once students have these tools in their tool belt, I start introducing higher-level texts. They’re gaining proficiency, but they are still struggling readers, and they’re not ready for the full independence of working with long texts on their own.

So I start to give them a little taste: an appetizer, if you will. To do this and to make the reading relevant to them, I get my texts snippets from their content area textbooks.

I bring these “appetizers” in to class and “serve” them at the beginning of class as our warm-up. To scaffold their reading, I give them a focused purpose. They may have to answer a question about the author’s purpose, or they may have to identify a text structure. It helps them to see that their practice work with the easier texts is helping them to approach the more daunting texts they see in their classes all the time.

Lessons for ELA Classrooms

Finding this balance is crucial not only in intervention classes like AARI, but in all reading. We know our students have some pretty high expectations set by the Common Core State Standards and assessments like the redesigned SAT. Teachers want students to be able to access their texts, but they also know the value of exposing them to more challenging options. To help achieve this balance, I’ve found that these steps are key:

- Arm students with tools to help them bridge the gap between accessible and challenging texts. Word banks are a great start.

- Introduce more difficult texts slowly and in small chunks.

- Gradually build to a combination of high-level, high-skill texts that require more stamina.

Megan Kortlandt is a secondary ELA consultant and reading specialist for the Waterford School District. In the mornings, she teaches AARI and literacy intervention classes at Waterford Mott High School, and in the afternoons, she works with all of Waterford’s middle and high school teachers and students in the Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment department. Additionally, Megan works with Oakland Schools as an instructional coach for AARI. She has presented at various conferences including the Michigan Council for Teachers of English and Michigan Reading Association annual conferences.

Megan Kortlandt is a secondary ELA consultant and reading specialist for the Waterford School District. In the mornings, she teaches AARI and literacy intervention classes at Waterford Mott High School, and in the afternoons, she works with all of Waterford’s middle and high school teachers and students in the Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment department. Additionally, Megan works with Oakland Schools as an instructional coach for AARI. She has presented at various conferences including the Michigan Council for Teachers of English and Michigan Reading Association annual conferences.

For my first triathlon, actually my only triathlon, I swam with a snorkel. Yes, you are allowed to do so, however you can not win. Being the disciplined athlete I am I was unencumbered by this restriction as I wheezed around the course.

For my first triathlon, actually my only triathlon, I swam with a snorkel. Yes, you are allowed to do so, however you can not win. Being the disciplined athlete I am I was unencumbered by this restriction as I wheezed around the course. Swimming is challenging for me. If the swim leg of a sprint triathlon was 50 yards, I would be fine, but it is not. It is 1/2 mile, which is a long, long way for me. The ride and the run are OK; note I did not say easy, or enjoyable.

Swimming is challenging for me. If the swim leg of a sprint triathlon was 50 yards, I would be fine, but it is not. It is 1/2 mile, which is a long, long way for me. The ride and the run are OK; note I did not say easy, or enjoyable. Effective feedback, grounded in where the learner is in the moment, is critical. It would be helpful, though not always essential, to have feedback from peers and/or a more knowledgeable other. However, in the end, it is the learner’s (my) responsibility for success. Interestingly, this raises the issue of goal setting, which is something for another day.

Effective feedback, grounded in where the learner is in the moment, is critical. It would be helpful, though not always essential, to have feedback from peers and/or a more knowledgeable other. However, in the end, it is the learner’s (my) responsibility for success. Interestingly, this raises the issue of goal setting, which is something for another day. Prior to coming to Oakland Schools in 2004, Les Howard worked as an independent consultant across the United States based in San Francisco. Les came to California in 1994 to help establish Reading Recovery in California. He has been an educator for almost 40 years, almost 20 years in Australia. During this time he has been an elementary teacher, assistant principal, and literacy consultant and district literacy coordinator. Les is also a trained Ontological Coach. He believes coaching is a powerful process that empowers educators. He loves being outdoors and loves bicycling hiking, paddling, triathlons and adventure races, and trying to tire out his border collie. He and his wife enjoy traveling and camping.

Prior to coming to Oakland Schools in 2004, Les Howard worked as an independent consultant across the United States based in San Francisco. Les came to California in 1994 to help establish Reading Recovery in California. He has been an educator for almost 40 years, almost 20 years in Australia. During this time he has been an elementary teacher, assistant principal, and literacy consultant and district literacy coordinator. Les is also a trained Ontological Coach. He believes coaching is a powerful process that empowers educators. He loves being outdoors and loves bicycling hiking, paddling, triathlons and adventure races, and trying to tire out his border collie. He and his wife enjoy traveling and camping.