Surprising librarian fact: many people assume that I love every book that I try to read. I wish that were the case. In fact, somewhat regularly, I find myself in the midst of a reading slump, reading several books in a row with which I just don’t connect.

Reading slumps can be deadly. They kill your desire to read, making you feel that any other pursuit might be more fun or productive.

But with time and practice, I have found a few techniques that can help me to break out of a reading slump. I find they also work pretty well on reluctant readers, who themselves may be in the middle of an epic, life-long reading slump that they now consider the status quo. Here are some slump-busters to try with your students (or yourself):

1. Try a book in a new format, preferably one that reads quickly.

Verse novels are becoming more common and have been quite popular with my students. The sheer amount of white space on any given page, combined with text that addresses topics in a more direct way, makes verse novels fast paced. This appeals to all kinds of readers.

One excellent verse novel that has been very popular with students across reading levels is The Crossover, by Kwame Alexander. It’s a coming-of-age verse novel that involves sibling rivalry, parental relationships, school drama, and grief. The main character, Josh and his twin, Jacob, are talented basketball players, so there are some excellent basketball scenes that could be read out of context. It’s also quick, engaging, and touching. I don’t think I’ve ever had a student dislike it.

2. Go back to a topic or genre that you’ve been neglecting.

I found myself caught in a mini-slump last year, during a period of heavy realistic fiction and professional reading. I didn’t necessarily dislike these, but I needed to refresh myself with something I hadn’t tried in a while.

Enter Every Heart a Doorway, by Seanan McGuire. This fantasy novella is filled with tremendous characters, fascinating backstory, and heaps of whimsy. I had been so caught up in big, heavy doses of reality that this little fantasy novel was a breath of fresh air.

Don’t get me wrong here: trying something totally new that you’ve never tried before is not a good strategy for sloughing off a slump. But returning to something that I had been missing was just what I needed to get back on my reading game.

3. Choose something funny.

It’s only been a few years since I realized that sometimes my slumps are not really about reading at all.

There have been many times in my life when the book that I was reading hit a little too close to home. I enjoy books about social movements, but sometimes the issues in my books pile on to the issues in real life, and that brings me down. I find that I’m not eager to get back to my book because it’s upsetting me or making me anxious.

This is the moment for a funny book. The playful tone in The Upside of Unrequited, by Becky Albertalli, really gave me a boost. The characters are all people I wish I knew in real life, and I found myself rooting for them. There is a sense of hopefulness imbued in the story, and the main character, Molly, has a charming, slightly self-deprecating voice that made me snort-laugh on at least one occasion. A funny book may not solve the world’s problems, but this one reinvigorated my spirit and fed my inner reader a hearty portion of comfort food.

4. Pick something that everyone else has LOVED

There is a risk of ending up with something that disappoints because it’s been over-hyped. Yet it can be very satisfying to pick up a book that everyone’s been talking about, and then to become part of the conversation.

Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere has been weaving its way through my high school (and the country) since the fall. It’s an adult novel, but the inclusion of five teenage main characters grappling with familial and community expectations has made it of great interest to my students.

In the end, even the most avid reader is bound to hit a slump occasionally. I’d love to know about readers’ favorite books that have helped them break out of a reading rut!

Bethany Bratney (@nhslibrarylady) is a National Board Certified School Librarian at Novi High School and was the recipient of the 2015 Michigan School Librarian of the Year Award. She reviews YA materials for School Library Connection magazine and for the LIBRES review group. She is an active member of the Oakland Schools Library Media Leadership Consortium as well as the Michigan Association of Media in Education. She received her BA in English from Michigan State University and her Masters of Library & Information Science from Wayne State University. Bethany is strangely fond of zombies in almost all forms of media, a fact which tends to surprise the people that know her. She has two children below age five, and is grateful at the end of any day that involves the use of fewer than four baby wipes.

Bethany Bratney (@nhslibrarylady) is a National Board Certified School Librarian at Novi High School and was the recipient of the 2015 Michigan School Librarian of the Year Award. She reviews YA materials for School Library Connection magazine and for the LIBRES review group. She is an active member of the Oakland Schools Library Media Leadership Consortium as well as the Michigan Association of Media in Education. She received her BA in English from Michigan State University and her Masters of Library & Information Science from Wayne State University. Bethany is strangely fond of zombies in almost all forms of media, a fact which tends to surprise the people that know her. She has two children below age five, and is grateful at the end of any day that involves the use of fewer than four baby wipes.

These are some of the comments I’ve heard over the years from boy readers. But, for every boy who makes remarks like these, there is a book that will save reading.

These are some of the comments I’ve heard over the years from boy readers. But, for every boy who makes remarks like these, there is a book that will save reading.

Lauren Nizol (

Lauren Nizol ( Recently I was teaching a demonstration lesson at Oakland University. I brought one of my students, Brandon (a pseudonym), who was among the lowest readers at the beginning of first grade. He had been in an intervention group all year with his first grade teacher and an additional group with me. Now in the spring, we were working one on one, as he still had not yet met grade-level standards.

Recently I was teaching a demonstration lesson at Oakland University. I brought one of my students, Brandon (a pseudonym), who was among the lowest readers at the beginning of first grade. He had been in an intervention group all year with his first grade teacher and an additional group with me. Now in the spring, we were working one on one, as he still had not yet met grade-level standards.

The other day, my eight year old was brimming with questions about the Revolutionary War. As I went through each, I found myself using vocabulary that he needed me to explain, like alliance–after which he quickly said, “Oh, I get it! My buddy is my alliance on the playground.”

The other day, my eight year old was brimming with questions about the Revolutionary War. As I went through each, I found myself using vocabulary that he needed me to explain, like alliance–after which he quickly said, “Oh, I get it! My buddy is my alliance on the playground.”

Lauren Nizol (

Lauren Nizol (

Strong words, right? Whenever I see the words hate and reading this close together, my skin crawls.

Strong words, right? Whenever I see the words hate and reading this close together, my skin crawls.

What’s more fun than reading a book set in a place with which you are intimately familiar? To read about restaurants, buildings, and even street names that you know personally is a small thrill.

What’s more fun than reading a book set in a place with which you are intimately familiar? To read about restaurants, buildings, and even street names that you know personally is a small thrill. James was spread out on one of the counters, with all his papers and materials circling his laptop. He smiled as I approached.

James was spread out on one of the counters, with all his papers and materials circling his laptop. He smiled as I approached.  Lauren Nizol (

Lauren Nizol ( I love historical fiction. Strangely, the reason I seem to love it most is that I find it humbling in two ways.

I love historical fiction. Strangely, the reason I seem to love it most is that I find it humbling in two ways. Bethany Bratney

Bethany Bratney The Great Graphic Novel Experiment is in full swing in my classroom. In fact, it has become the focal point of my passions this year. I’ve been so vocal about it that my wife and kids actually bought me a couple graphic novels for my birthday. I’m “all in,” as Matt Damon says in the film Rounders.

The Great Graphic Novel Experiment is in full swing in my classroom. In fact, it has become the focal point of my passions this year. I’ve been so vocal about it that my wife and kids actually bought me a couple graphic novels for my birthday. I’m “all in,” as Matt Damon says in the film Rounders. I could go on, but I think the broader point is more important: these are stories that will speak to any reader. I passed along two of the aforementioned titles to other people in my department, who sent back rave reviews—and then sent along new titles of their own! Nimona, a work of fantasy, and the graphic novelization of Mrs. Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children are now in my queue.

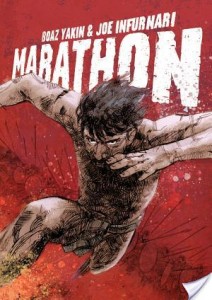

I could go on, but I think the broader point is more important: these are stories that will speak to any reader. I passed along two of the aforementioned titles to other people in my department, who sent back rave reviews—and then sent along new titles of their own! Nimona, a work of fantasy, and the graphic novelization of Mrs. Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children are now in my queue. And what’s more, other research hints that such visual reading may also maximize a reader’s ability to retain information. That might not seem like a key merit for pleasure reading. But consider how many graphic novels have been written about historical events and culturally relevant topics: Marathon, about the Greek tale of that famous run; Templar, about what became of that famous secret society; and Americus, about censorship in literature. They’re all fiction, but still dense with contextual facts that the research suggests students will retain.

And what’s more, other research hints that such visual reading may also maximize a reader’s ability to retain information. That might not seem like a key merit for pleasure reading. But consider how many graphic novels have been written about historical events and culturally relevant topics: Marathon, about the Greek tale of that famous run; Templar, about what became of that famous secret society; and Americus, about censorship in literature. They’re all fiction, but still dense with contextual facts that the research suggests students will retain.