For the next two years, I will be part of the Galileo Leadership Consortium, which works to advance teacher leadership. In this role, I am asked to learn that I can do better for the profession.

For the next two years, I will be part of the Galileo Leadership Consortium, which works to advance teacher leadership. In this role, I am asked to learn that I can do better for the profession.

Sometimes all we have to realize is that we only have to know that we can do better. And one of the things that the consortium believes we can do better is grading. We believe that grading doesn’t have to be punitive, and that it can actually relay information about what a child has learned. To help you understand and implement these beliefs, I will share the information I have learned from experts, and how I have used that learning in my 8th grade Language Arts classroom.

Wormeli’s Views of Grading

The first expert I encountered was Rick Wormeli. He is best known for his research on 21st-century teaching practices. Five minutes into a day with him, though, and you realize that he has used all of the research that he presents.

From Wormeli, I learned three things:

- Teachers are ethically responsible for the grades which they report.

This means that grades that are padded—with scores for neatness, following directions, turning work in on time—are grades that do not represent the amount of learning the student has achieved.

- Grades should accurately report the amount of mastery that a student has on the standards of that subject.

This means that an A in Language Arts represents that the student has achieved an A level of mastery in the reading and writing of narrative, argument, and information. An A level of mastery is typically coined by the terms “Exceeding Mastery.”

- Assessments should be connected to standards.

This means that all activities that we ask of students should be related to the learning they should be achieving. So, every assessment should be connected to a standard, so the student’s grade can reflect the achievement of that standard.

What This Looks Like in My Classroom

So, what does standards-based grading mean in literacy instruction, and what does this look like in my classroom?

I don’t have a definitive answer, but I have some experiences that I will share.

Shift 1: I connect daily lessons to standards, and present these connections to students.

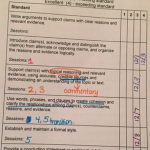

At the beginning of each lesson, I name my teaching point. Students and I refer to our Self-Evaluation Standards page (you can click on the thumbnail image to the right). On this page, we underline key words and compare how our work achieved that standard. As you can see, the columns represent achievement levels. Students can mark a date and a level they think they achieved. From here, students can see their growth towards achieving each standard.

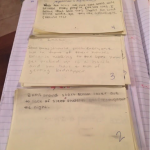

Shift 2: For every standard that I teach to kids, I create a rubric of achievement.

I share the rubrics with kids along with exemplars (thumbnail on the right) of each achievement level. Students can see where their work aligns with that of their peers and the way work should look. The rubric and examples help kids to work to meet the standards.

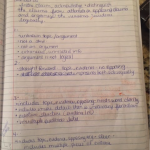

Shift 3: I insist that students walk away each day having learned something.

In order to quantify this, I have started giving quick and varied formative assessments. For one  concept, it may be a post-it of key terms, with verbal descriptive feedback. For another concept, it may be written descriptive feedback about how to move forward in achieving a standard (an example is on the right). For any assessment, students may re-try the work, in order to show more learning. This helps kids learn and apply the material, but it also shows them that they are active learners, and learners who are successful.

concept, it may be a post-it of key terms, with verbal descriptive feedback. For another concept, it may be written descriptive feedback about how to move forward in achieving a standard (an example is on the right). For any assessment, students may re-try the work, in order to show more learning. This helps kids learn and apply the material, but it also shows them that they are active learners, and learners who are successful.

Every day in my classroom looks a little different. And I am using different strategies to reach all of my learners. But in doing so, I know what standard that students have achieved and what standard they are working on. We also have a great community that wants to work and grow and show their best work. And all this came from three small shifts.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.