My kids took the AP US History Exam last month, so now is a good time to reflect on a writing experiment I led this year.

If you read my first post, you’ll recall that I described HistoryHive (then known as HerodotusHive) as a structured space where my APUSH students would go to improve their writing. There, APUSH alumni (now juniors and seniors) would share insights—essentially craft knowledge—with my current students on how to build on all of the class work we’ve done to write for APUSH.

In my second post, I explained that the HistoryHive is premised on the work of physics professor Eric Mazur, who found that at a certain point in the learning process, peer instruction helped his students in ways he could not.

I had an open question going in. Mazur’s world is of one of equations and right answers with decimal points. Would this method transfer to writing?

5 Parts to the Hive

We’ve had a total of 10 HistoryHives since the fall. Structure was important. I couldn’t just have current students and former students show up and say, “Go!” So, each Hive featured 5 distinct parts:

1. I review the targeted writing skill, with my flipped lecture.

2. Mentor Historians riff tips about the targeted skill.

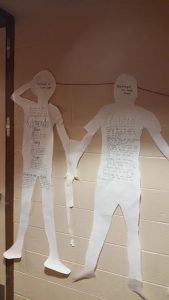

3. In small-group settings, Apprentice Historians discuss a piece of writing with Mentor Historians.

4. All together, we debrief about epiphanies.

5. Apprentice Historians can stay after for Franchi Flash Feedback.

The result? I could tell that Mazur’s method did in fact transfer to writing.

Not to sound cheesy here, but from the beginning of the year until the end, there really was a buzz in the Hive. I saw lots of kids walk through the door; I saw buy-in; I saw focus; I saw a genuine drive to be better writers. I heard great conversations about writing. And I saw growth taking place in real time.

It was so satisfying to see students show up without the dangle of extra credit. OK, I have to confess: I may have offered snacks. But the point is that the kids were invested for all the right reasons. I certainly thought it went well. But what did the kids say?

Ah-Ha! Moments

During a riffing segment on introductions, Apprentice Historian Christine (a pseudonym, as with others) learned that “it’s important for us to ask ourselves what someone would need to know before reading our essay.” This moment of advice from a mentor stuck out. “It improved my writing dramatically and months later I still ask myself this question before I write an introduction,” she told me.

I noticed that any given piece of advice might not be needed by most, but individual students were catching on with “Ah-Ha” moments. For Dakota, that moment was when she realized she needed to focus on the significance of the documents instead of summarizing them. Sara picked up something about sentence structure. For others, the importance of planning and using the language of historians like “turning point” were the lessons that stuck.

In one Hive about mid-year, we had a collective “ah-ha!” moment, the one that seemed to resonate with most. See a pattern?

Realizations about Depth

“CK [Content Knowledge] can be used really well, or really horribly. For CK you can’t just spill a bunch of it out on paper and expect it to be relevant to the topic,” Juliette told me.

The key, Nicole learned, was to “have a few strong pieces and spend most of my time analyzing them.” Ellen agreed, saying it’s all about “quality, not quantity.” And so did Don, recalling that the best tip from the year was to “just answer the question directly and don’t add extra ‘fluff’ just to make your essay seem longer.” Candice, a Mentor Historian, reported that this was a point she made with groups, urging students to only “provide those specific events that would help build your argument.”

Haruto, another Mentor Historian, was the one who started a conversation about this for the whole Hive. I could tell he was on to something when I saw lots of nodding around the room. He said that “the deeper analysis you have of your CK is much better than having a bunch of CK with shallow analysis.”

This lesson underscores the real progress kids can make in understanding their task for advanced writing. Many kids come into the course conditioned to believe that simply stacking content knowledge is the way to prove their points. In a class like APUSH, the effect is a show-and-tell of topics learned, when the reality is that they need to offer analysis. The sooner kids can shed those old ways of thinking about school, the more they’ll grow into more sophisticated writers.

And, it turns out, these are lessons they can learn from each other–perhaps even more so than from me.

Rod Franchi (@thehistorychase) is in his 21st year teaching Social Studies at Novi High School. He did his undergraduate work at Albion College and the University of Michigan, and earned an M.A. in English at Wayne State University and an M.A. in History Education at the University of Michigan. Having served as an education leader at the school, district, county, and state levels, Rod now works as AP US History Consultant and AP US History Mentor for the College Board. He is also Co-Director of the Novi AP Summer Institute and is an Attending Teacher in the University of Michigan’s Rounds Program.

Rod Franchi (@thehistorychase) is in his 21st year teaching Social Studies at Novi High School. He did his undergraduate work at Albion College and the University of Michigan, and earned an M.A. in English at Wayne State University and an M.A. in History Education at the University of Michigan. Having served as an education leader at the school, district, county, and state levels, Rod now works as AP US History Consultant and AP US History Mentor for the College Board. He is also Co-Director of the Novi AP Summer Institute and is an Attending Teacher in the University of Michigan’s Rounds Program.

Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for

Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for  I used to think that nonfiction was not my thing. But I’m a librarian, so I have to make it my thing in order to best serve my students and staff. Still, I often felt like I was twisting my own arm while reading nonfiction.

I used to think that nonfiction was not my thing. But I’m a librarian, so I have to make it my thing in order to best serve my students and staff. Still, I often felt like I was twisting my own arm while reading nonfiction. Bethany Bratney

Bethany Bratney In my first post, I described some writing problems that surfaced in my AP US History classroom, as well as

In my first post, I described some writing problems that surfaced in my AP US History classroom, as well as  One of the cool things about teaching is that each year is a new season. After all the reflecting and conversations about what worked and what didn’t, we get to design new plans and start fresh in September.

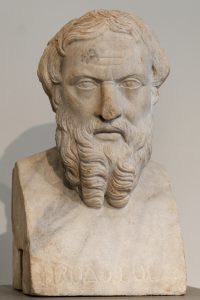

One of the cool things about teaching is that each year is a new season. After all the reflecting and conversations about what worked and what didn’t, we get to design new plans and start fresh in September. That spark from Corey’s offer helped me come up with a new plan. I’m calling it HerodotusHive.

That spark from Corey’s offer helped me come up with a new plan. I’m calling it HerodotusHive.