Examples of students’ character cutouts

I have a love/hate relationship with this time of year.

We’re in full swing with the end-of-year craziness. Yet this also is the time when I teach the American Revolution in social studies. I’m able to combine the content with our historical fiction unit in reading, and our opinion unit in writing. This is a wonderful opportunity to combine content areas and provide a truly immersive experience for my students.

It is so nice to have a seamless day of reading both fiction and nonfiction texts around this topic, and having conversations that span reading, writing, and social studies. I find that I am excited about teaching, and students are excited about learning. It’s no small feat at this time of year!

What The Unit Looks Like

Right now in the hallway are cutouts of characters from our read aloud and our book club books. Within the cutouts are character traits and reflections about critical choices, power, and how these characters were shaped by the times in which they lived. Connecting all of the characters is a red string, and tomorrow students are going to spend time reading the cutouts and making connections. Then we will write them on paper that will hang from the string, making our thinking visible. This is a new project but one whose outcome I am super excited to see.

Another project that I always do during this time of year is a thinking routine from Ron Ritchhart called a “step inside.” This writing project combines the best parts of narrative writing, yet allows students to use their imagination to step inside the life of a slave from the 1500s. As students examine the three phases of slavery as outlined in our text, they attempt to step inside and develop empathy for the experience of these people. This is a lengthy writing assignment and yet one that is incredibly powerful. I have had students tell me it is their favorite writing assignment of the year.

I find that students actually are able to bring more elements of narrative writing in this assignment than they sometimes are able to do in their own pieces. I think this is because of the scaffolding required for the assignment. Also, the assignment requires that they pay attention to a number of details, which enables them expand their normal writing habits.

Integrating Opinion Writing

The opinion writing comes very late in May and in early June. This is when students have to take a side in the American Revolution. They are assigned either the Patriot side or the Loyalist side, and they have to defend their side based on evidence from their historical-fiction text. They also rely on the supplemental reading we do with nonfiction texts.

The opinion pieces have to include a counter argument acknowledging the position of the other side. Yet they also have to defend their own positions and attempt to persuade the reader to agree with them. All of this is used in a real-life debate with a student moderator, and the kids absolutely love it!

As I write this we are at the end of an unusually warm (86 degrees!) day in May. I have a huge to-do list and yet I am still excited about all that is going on in my classroom. All of this gets me wondering how I can channel this same type of integration and excitement into the rest of my year. Perhaps this will become my summer project: examining my curriculum to find better connections and texts that will lend themselves to this cross-curricular type of integration. My wheels are already spinning.

Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for Clarkston Community Schools, where she has been teaching full time since 2006. She is blessed to teach Language Arts and Social Studies for her class and her teaching partner’s class, while her partner teaches all of their math and science. This enables them to focus on their passions and do the best they can for kids. Beth was chosen as Teacher of the Year for 2013-2014 in her district. She earned a B.S. in Education at Kent State University and a Master’s in Educational Technology at Michigan State University.

Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for Clarkston Community Schools, where she has been teaching full time since 2006. She is blessed to teach Language Arts and Social Studies for her class and her teaching partner’s class, while her partner teaches all of their math and science. This enables them to focus on their passions and do the best they can for kids. Beth was chosen as Teacher of the Year for 2013-2014 in her district. She earned a B.S. in Education at Kent State University and a Master’s in Educational Technology at Michigan State University.

In my first post, I described some writing problems that surfaced in my AP US History classroom, as well as

In my first post, I described some writing problems that surfaced in my AP US History classroom, as well as  Rod Franchi (

Rod Franchi ( One of the cool things about teaching is that each year is a new season. After all the reflecting and conversations about what worked and what didn’t, we get to design new plans and start fresh in September.

One of the cool things about teaching is that each year is a new season. After all the reflecting and conversations about what worked and what didn’t, we get to design new plans and start fresh in September. That spark from Corey’s offer helped me come up with a new plan. I’m calling it HerodotusHive.

That spark from Corey’s offer helped me come up with a new plan. I’m calling it HerodotusHive. At the start of December, I attended a workshop at the Detroit Port Authority Lofts, which, it turns out, is an event space, not a place where ships check in. I’ve lived in southeast Michigan my entire life, and spent many, many hours in the city. But I didn’t know this place was there. I thought, The city of Detroit is like teachers: there’s so much good stuff happening, but no one knows about it, or the ones who do know treat the information like it’s secret.

At the start of December, I attended a workshop at the Detroit Port Authority Lofts, which, it turns out, is an event space, not a place where ships check in. I’ve lived in southeast Michigan my entire life, and spent many, many hours in the city. But I didn’t know this place was there. I thought, The city of Detroit is like teachers: there’s so much good stuff happening, but no one knows about it, or the ones who do know treat the information like it’s secret.

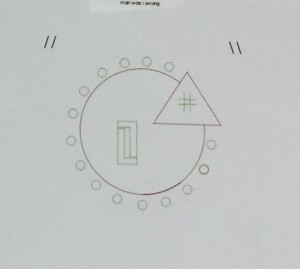

were learning about conics. With that, they created logos for us to vote on. Most of my department picked the logo shown on the right. It reflected our desire to have a design that opened a conversation, by provoking a person to ask about the logo. The shapes are meant to represent aspects of our discipline and practice. We didn’t want books or pens or apples. Too

were learning about conics. With that, they created logos for us to vote on. Most of my department picked the logo shown on the right. It reflected our desire to have a design that opened a conversation, by provoking a person to ask about the logo. The shapes are meant to represent aspects of our discipline and practice. We didn’t want books or pens or apples. Too  Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a

This experience showed me and Doug that it is imperative for disciplines to collaborate. Neither of us could have gotten the quality of work the students produced had we done this separately. For the first time, students were seeing exactly how the skills they learn in their individual classes apply to all classes. They were developing skills–research skills, presentation skills– not just memorizing facts and figures.

This experience showed me and Doug that it is imperative for disciplines to collaborate. Neither of us could have gotten the quality of work the students produced had we done this separately. For the first time, students were seeing exactly how the skills they learn in their individual classes apply to all classes. They were developing skills–research skills, presentation skills– not just memorizing facts and figures. Lisa Kraiza teachers eighth grade English Language Arts at Oak Park Preparatory Academy. She is also a member of the Core Leadership Team of the

Lisa Kraiza teachers eighth grade English Language Arts at Oak Park Preparatory Academy. She is also a member of the Core Leadership Team of the