From my earlier blog posts, you know that I have a workshop classroom where the notebook rules all. Like many of you, every piece of paper I give students is taped into notebooks and meticulously labeled. The notebooks hold the intricacies of the strenuous work of writing and the empathy of reading. Each student’s notebook is their own. In their notebooks, students can be their very best and sometimes even their worst. They can be an artist. They can be an author. They can be an editor. They can be themselves.

And they are.

But now our whole world, our 8th grade Language Arts world, our writing community, has a new resident that we are not sure about. This new resident has brought a change to our community that affects our very being. In a time of change, my personal belief is that writing is an excellent release and the consistency of a notebook is a place of comfort. Yet, this visitor doesn’t consistently allow us this comfort. My school implemented a 1:1 iPad program in grades 6-8 around Thanksgiving.

There is a definite air of excitement regarding this new device. Students are cautious, yet fearless. Teachers are careful, yet innovative. On the one hand, I am a tech-person who hopes to teach kids new thought processes not just new apps; on the other hand, I love the act of handwriting and the thinking that comes with that physical work. But these new devices cause me to question: Is the world of handwritten notebooks relevant anymore? What is the best use of iPads for notebook work? And finally, what does a transformative digital language arts workshop classroom look like?

What is the answer?

Unfortunately, I don’t have a definitive answer for the use of iPads on a daily basis for Language Arts instruction, but I will share with you some ways I have used them and what has come of their use in my classroom.

The school release of iPads goes hand-in-hand with our opportunity to be a Google School that uses Google Apps for Education. I’ve been an advocate for the use of Google apps in the classroom for many years now, so it was an easy decision to jumpstart of iPad use in the classroom by diving into Google Apps and programs before moving to other tools. Each time I use technology with kids, I hope to increase their digital citizenship knowledge by introducing them to tools and ways of thinking that they can use outside of my classroom as well. Google Apps were a perfect place to start.

Tool: Google Classroom

This tool is exclusively available for Google Education users and manages class lists and links to student’s Google Drive accounts.

This tool is exclusively available for Google Education users and manages class lists and links to student’s Google Drive accounts.

The advertised benefits:

- Sharing digital documents with a whole class that puts copies into students’ Drive folders.

- Class lists help the teacher manage students’ work submissions.

- Discussion threads allow interaction between classmates and teacher.

How I planned to use it: To distribute daily tape-ins (handouts that students tape into their writer’s notebooks).

What I think: I think this is a good tool to use for students to turn in summative projects. It’s not effective for sharing out materials with kids because it creates a very messy Drive for teacher and students. Classroom also fails to provide the opportunity to teach digital citizenship skills or online organization.

What students think: Currently, there is confusion between using Classroom to search for assignments and our district mandated Moodle pages. Students feel that it is a bit time consuming.

Tool: Google Drive

This platform houses online documents that can be created, shared, and collaborated on.

This platform houses online documents that can be created, shared, and collaborated on.

The advertised benefits:

- Never lose a document again and have access to all documents that you may need at your fingertips.

- It also allows collaboration and unlimited sharing of documents.

How I planned to use it: After my experiences with Google Classroom, I transferred to sharing documents with kids via Drive. I taught them how to organize their Drive into folders and name documents.

What I think: This is a good platform to use to share documents with contacts. It is also relevant for teaching students how to organize digital work. However, if students want to write on a tape-in, like we have in our notebooks, they have to copy the text I share and create a new document. This allows them to edit the document.

What students think: Overall, they like the opportunity to have all their documents online. They are at a variety of places concerning this work. Some students are all online – using Drive for everyday work in Language Arts. Some students use tape-ins in notebooks and work online. Some are all hard copy notebooks. I allow students this variety and choice.

Tool: Evernote/Penultimate

This program’s purpose is online organization and notebook creation. Penultimate is an Evernote sister app which syncs data but also allows handwritten notes.

This program’s purpose is online organization and notebook creation. Penultimate is an Evernote sister app which syncs data but also allows handwritten notes.

Advertised benefits:

- Consistently syncs and backs up data, has several Google tie-in programs and a stylus appears like actual handwriting.

How I planned to use it: We could create digital notebooks much the same as our paper copies.

What I think: While not transformative, this app has potential as a digital writer’s notebook, but the program is rudimentary. It needs additional features like cropping pictures and more precise writing (even with the joint Stylus).

What students think: They would rather use their notebooks.

To learn more about handwritten digital writers notebooks with Penultimate, read this blog post by Two Writing Teachers.

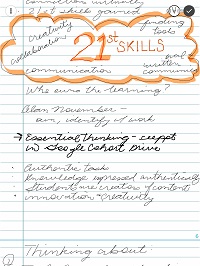

a writer’s notebook page in Penultimate

In the end, I am playing with the programs and listening to my students, but I don’t have a definitive answer. Rather, I have a question for you: What do you think of writer’s notebooks in a digital world? And how are you handling them in your classroom?

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.

This tool is exclusively available for Google Education users and manages class lists and links to student’s Google Drive accounts.

This tool is exclusively available for Google Education users and manages class lists and links to student’s Google Drive accounts. This platform houses online documents that can be created, shared, and collaborated on.

This platform houses online documents that can be created, shared, and collaborated on. This program’s purpose is online organization and notebook creation. Penultimate is an Evernote sister app which syncs data but also allows handwritten notes.

This program’s purpose is online organization and notebook creation. Penultimate is an Evernote sister app which syncs data but also allows handwritten notes.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the  We’ve reached the point in my 8th grade classroom where we’ve modeled, practiced, and established norms that we can use in our workshop classroom. Additionally, I have also conferenced with each student to give them a next step as they continue their reading and writing work. This, however, is not a blog post about effective conferencing, rather it’s about what I’ve learned from conferencing with a particular student. This experience leaves me wondering whether we, as teachers, always realize the effects we have on students?

We’ve reached the point in my 8th grade classroom where we’ve modeled, practiced, and established norms that we can use in our workshop classroom. Additionally, I have also conferenced with each student to give them a next step as they continue their reading and writing work. This, however, is not a blog post about effective conferencing, rather it’s about what I’ve learned from conferencing with a particular student. This experience leaves me wondering whether we, as teachers, always realize the effects we have on students? Amidst these in-class conferences with Kyle, I met Kyle’s mom. She shared a story with me about a 3rd grade teacher who told Kyle that he was not a writer. While I’m not writing this post to place blame, I see that when Kyle sits down to write, he does so with doubt. This doubt may have come from the seed planted by that teacher, but it probably also came from many other writing experiences that perhaps didn’t go as Kyle had hoped. In the end, Kyle had a very successful first writing unit in my classroom, and I hope that he’ll continue to feel excited about writing as we get into argument and informative writing. But this whole episode left me wondering–what effects do we, as teachers, have on students?

Amidst these in-class conferences with Kyle, I met Kyle’s mom. She shared a story with me about a 3rd grade teacher who told Kyle that he was not a writer. While I’m not writing this post to place blame, I see that when Kyle sits down to write, he does so with doubt. This doubt may have come from the seed planted by that teacher, but it probably also came from many other writing experiences that perhaps didn’t go as Kyle had hoped. In the end, Kyle had a very successful first writing unit in my classroom, and I hope that he’ll continue to feel excited about writing as we get into argument and informative writing. But this whole episode left me wondering–what effects do we, as teachers, have on students? Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the

This experience showed me and Doug that it is imperative for disciplines to collaborate. Neither of us could have gotten the quality of work the students produced had we done this separately. For the first time, students were seeing exactly how the skills they learn in their individual classes apply to all classes. They were developing skills–research skills, presentation skills– not just memorizing facts and figures.

This experience showed me and Doug that it is imperative for disciplines to collaborate. Neither of us could have gotten the quality of work the students produced had we done this separately. For the first time, students were seeing exactly how the skills they learn in their individual classes apply to all classes. They were developing skills–research skills, presentation skills– not just memorizing facts and figures. Lisa Kraiza teachers eighth grade English Language Arts at Oak Park Preparatory Academy. She is also a member of the Core Leadership Team of the

Lisa Kraiza teachers eighth grade English Language Arts at Oak Park Preparatory Academy. She is also a member of the Core Leadership Team of the  This moment is different from the beginning of school, when everyone is excited to be back. This moment happens after my sixth grade students start to remember that:

This moment is different from the beginning of school, when everyone is excited to be back. This moment happens after my sixth grade students start to remember that: Then it happens. It is like the compact florescent lamps (CFLs). You know, the energy efficient bulb that turns on and takes a minute to become its brightest self. The light coming toward me gets brighter… (As you read this, you may think one of two things is about to happen – I am going to be wonderfully surprised or run over by that train.) The light gets brighter and brighter and suddenly, guess what? The lights are bright all over the classroom! Even Mayze, Dion, Ann, and George are completely engaged and the air in the room shifts.

Then it happens. It is like the compact florescent lamps (CFLs). You know, the energy efficient bulb that turns on and takes a minute to become its brightest self. The light coming toward me gets brighter… (As you read this, you may think one of two things is about to happen – I am going to be wonderfully surprised or run over by that train.) The light gets brighter and brighter and suddenly, guess what? The lights are bright all over the classroom! Even Mayze, Dion, Ann, and George are completely engaged and the air in the room shifts. I breathe a sigh of relief that it was not a train, but rather brains becoming adjusted to thinking and considering and probing and analyzing. The air becomes full of questions and hypotheses. Understanding and synthesizing information becomes the order of the day. New ideas, new connections. Oh my! Light bulbs start turning on all over the room. I breathe in this creative air and in my head I scream “Yes!”

I breathe a sigh of relief that it was not a train, but rather brains becoming adjusted to thinking and considering and probing and analyzing. The air becomes full of questions and hypotheses. Understanding and synthesizing information becomes the order of the day. New ideas, new connections. Oh my! Light bulbs start turning on all over the room. I breathe in this creative air and in my head I scream “Yes!” Marcia Bonds is a 6th Grade Math and English Language Arts Teacher at Key School in the Oak Park School District. She has been teaching for 17 years. Marcia is a member of the Core Leadership Team of the

Marcia Bonds is a 6th Grade Math and English Language Arts Teacher at Key School in the Oak Park School District. She has been teaching for 17 years. Marcia is a member of the Core Leadership Team of the  As teachers, we all have students who are compliant and willful, who will readily produce whatever output we ask or demand of them to please the teacher or earn a desired grade. There is no question that narrative and non-fiction writing are critical skills that must be taught explicitly at all levels every year. Increasingly, however, in an era of online publishing and digital content production on social media sites, students need to know that whatever they are asked to generate will have a meaningful audience and make a difference to someone. In 2014, kids have never known a world where they haven’t been able to reach out around the globe in seconds and make an impact with words, pictures, and video on Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook. The ability to publish at the click of a button has provided a liberating opportunity for students to receive swift feedback and effectively measure the impact their writing has on their intended audience.

As teachers, we all have students who are compliant and willful, who will readily produce whatever output we ask or demand of them to please the teacher or earn a desired grade. There is no question that narrative and non-fiction writing are critical skills that must be taught explicitly at all levels every year. Increasingly, however, in an era of online publishing and digital content production on social media sites, students need to know that whatever they are asked to generate will have a meaningful audience and make a difference to someone. In 2014, kids have never known a world where they haven’t been able to reach out around the globe in seconds and make an impact with words, pictures, and video on Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook. The ability to publish at the click of a button has provided a liberating opportunity for students to receive swift feedback and effectively measure the impact their writing has on their intended audience. We all know that technology tools are constantly evolving and changing. What will remain immutable, however, is the architecture of story–problem, solution, characters, and setting. As long as we enable our students to make choices about the multi-modal output they would like to try, they will be motivated to learn the fundamental writing skills they need to grow and develop as writers. Students are empowered by both multi-media tools and the allure of a wider audience. Their work will have meaning for the maximum number of people possible, as it should. Kids care about writing and creating when they know people pay attention to and care about their work, that their writerly voices will be heard.

We all know that technology tools are constantly evolving and changing. What will remain immutable, however, is the architecture of story–problem, solution, characters, and setting. As long as we enable our students to make choices about the multi-modal output they would like to try, they will be motivated to learn the fundamental writing skills they need to grow and develop as writers. Students are empowered by both multi-media tools and the allure of a wider audience. Their work will have meaning for the maximum number of people possible, as it should. Kids care about writing and creating when they know people pay attention to and care about their work, that their writerly voices will be heard.