It’s testing season and stress is at an all-time high. But the past few years, I’ve started to notice an alarming trend. The students aren’t stressed about their stress; they celebrate it.

On test days, an AP student will drag into class and proudly proclaim that he was up until 3:00 a.m. studying. Not to be outdone, a fellow student will counter that she slept for three hours–midnight to 3:00–and then got up to continue studying. And they’re not lying.

I get more emails from my students between the hours of midnight and 6:00 a.m. than any other time. They chug coffee and Red Bull. They give up activities they truly love in favor of more studying and more test prep.

Happiness and a balanced life? Totally lame. Stressed and miserable? Badge of honor.

A Culture of Overworking

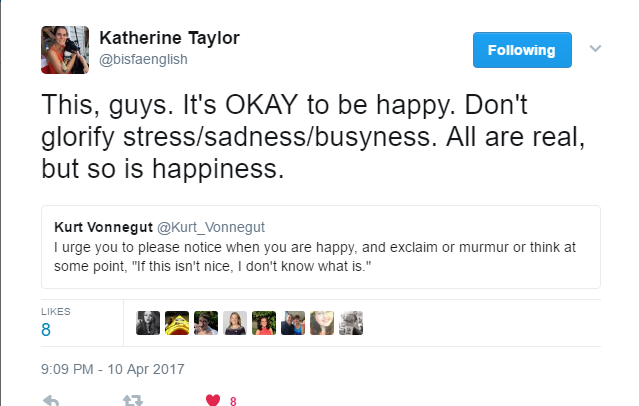

I know it’s not just my school. The other day a fellow English teacher in another school tweeted this to her students:

On the same day I saw her tweet, I read this New York Times piece about how a high school in Massachusetts is working to combat stress among its students.

And it’s not just high school students. In my Twitter feed, this opinion piece about our culture’s celebration of overworking popped up. Why wouldn’t our kids wear stress like a badge of honor? We do.

I think English teachers have a unique opportunity to do something about the stress we see in our students. We can’t change the culture of overwork and stress completely, but we can set our students up to better manage it.

Writers’ Notebooks

One of the easiest places to open the conversation about stress and workload is in the students’ writers’ notebooks. I think we need to be careful about how we frame those writing invitations, though. Inviting students to write about their stressors might be an opportunity to unload and unburden themselves, but it might be just one more chance for them to glorify their stress. Instead, frame reflective writing opportunities around stressors, successes, and plans.

Recently, my AP Seminar students returned to school on a Monday after a weekend of completing drafts of a major essay. The stress in the room was palpable when they entered. We started with our notebooks:

What’s something you’re happy about with your writing?

What is something that’s stressing you out about your writing?

What is the next step in your plan?

Verbally, I urged the kids not to skip a question or respond with one-word answers. As they wrote, I walked around and encouraged those who were struggling to find something good, and engaged those who couldn’t see a next step.

By the time we were done with our notebooks, the tension had eased and they were ready to dig into their drafts. If we are mindful about creating opportunities for students to work through their stress, hopefully they’ll be able to do it independently, too.

Standards-Based Grading

A broader consideration for reducing stress is in how we grade.

Though we are all eager to focus on the learning and to discount the letter grades, many of our students (and often their parents) are most concerned with their grades. As English teachers, we are uniquely situated to move toward standards-based grading because so much of our curriculum focuses on skills rather than content. If our students begin to see our classes as opportunities to practice skills and grow over the course of the year, perhaps individual assignments will begin to feel less like a hammer drop.

For example, in AP Language and Composition, I needed to prepare my students to write three different styles of essays. Throughout the second semester, we probably wrote four or five of each type. We conferenced about them, we self-assessed, we peer reviewed, and the writing improved over time. Through it all, students knew they would have multiple chances to improve and show me what they could do. When it finally came time to make one “count,” the pressure was significantly lower than if I had been counting them all along.

Modeling

One final way we can help our students manage stress is through our own modeling.

English teachers are notorious for dragging home bags and bags of essays. And, if you’re anything like me, you’re probably guilty of telling your students how buried you are in papers.

However, do we share enough of the ways we find balance in our own lives? Do we find balance in our own lives? If we do, we should share it with them. Tell them about how we pushed the stack of papers aside last night and stayed up reading–not a required novel but something we loved. Or even better? Tell them how we pushed the papers aside and played outside with our kids. If you don’t do those things, it’s time to start.

On that note, it’s a beautiful day. I’m going for a run.

Hattie Maguire (@TeacherHattie) is an English teacher and Content Area Leader at Novi High School. She is spending her sixteenth year in the classroom teaching AP English Language and Composition, AP Seminar and doing Tier 2 writing intervention. She is a National Board Certified Teacher who earned her BS in English and MA in Curriculum and Teaching from Michigan State University.

Hattie Maguire (@TeacherHattie) is an English teacher and Content Area Leader at Novi High School. She is spending her sixteenth year in the classroom teaching AP English Language and Composition, AP Seminar and doing Tier 2 writing intervention. She is a National Board Certified Teacher who earned her BS in English and MA in Curriculum and Teaching from Michigan State University.

I’d been experimenting with standards-based grading, gradually building trust with a group of seniors I’ve had for two years by “respecting their learning process.” I’d ask them to read something, negotiate a time frame, and I’d plan based on the assumption that they’d come prepared.

I’d been experimenting with standards-based grading, gradually building trust with a group of seniors I’ve had for two years by “respecting their learning process.” I’d ask them to read something, negotiate a time frame, and I’d plan based on the assumption that they’d come prepared.  I created two paths for students to demonstrate their skills. One was the Harkness option for students who’d read. Student’s who weren’t comfortable with that, for whatever reason, were assigned a series of dialectical journal entries which I’d read and grade.

I created two paths for students to demonstrate their skills. One was the Harkness option for students who’d read. Student’s who weren’t comfortable with that, for whatever reason, were assigned a series of dialectical journal entries which I’d read and grade. Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a