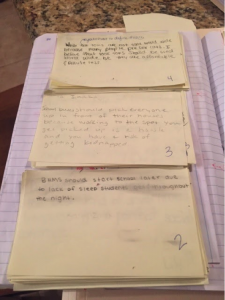

Research reveals that a score of zero, in a 100-point grading scale, is pretty difficult for a student to overcome. For example, if a student gained a zero for not having turned in work, he or she would have to turn in nine assignments, earning 100 points each, to overcome the impact of that zero score.

Research reveals that a score of zero, in a 100-point grading scale, is pretty difficult for a student to overcome. For example, if a student gained a zero for not having turned in work, he or she would have to turn in nine assignments, earning 100 points each, to overcome the impact of that zero score.

Many teachers just excuse the task, rather than assigning a zero for no work done. But this suggests that the tasks themselves are not valuable, and that the student should not have a grade that represents their learning.

To avoid the zero mark, teachers should take another approach: providing an additional opportunity for students to show their work.

#nozeros

To act on these ideas, I started a lunch routine called #nozeros. (The name came from a kid’s suggestion for a classroom assignment, and it helped to entice the kids to the event.)

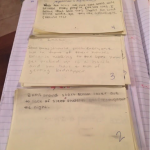

Here’s how it works. When students don’t turn in an assignment in class like a monthly reading log, I give them a lunch pass with #nozeros written on it. This requires them to spend a lunch in my classroom.

At first, students came reluctantly when they were given these passes. They expected a punishment-type lunch with the teacher.

Instead, they came and realized that I just wanted to give them a score on their work, and that I would help them if they liked. They could also work alone if they prefered.

If, for example, the missed assignment is a reading log, students write a claim about something that happened in their book. This task shows me that students have read the book, and it takes about a minute to complete. Students can leave when they finish, though some choose to stay and hang out.

These lunches have become something fun, and as my husband, a self-described average student, observes, “It’s not that they don’t want to do the assignment or can’t do the assignment. It’s that they forgot at night or don’t want to do it at home. They love this option because it gets their work in.” For me, the lunches make sense because I get work and students get a viable alternative to show that work.

Now, I have no zeros in my grade book and a lunch routine of openness and growth with my students.

The Growth Mindset

This kind of routine is part of my conscious effort at establishing a growth mindset in my classroom. I want students to realize that they can do their best work—and that sometimes this takes multiple attempts.

To help establish the growth mindset in my classroom this year, I also started modeling the work for my current students, and modeling work at all levels of achievement. All of my students’ work can be revised and resubmitted for feedback.

In addition to the #nozeros meetings, I opened my classroom at lunch time to offer kids one-on-one help if they desired.

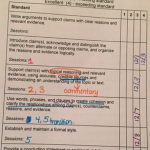

One student, Matt, became a weekly participant, with a goal to increase his level of achievement on our weekly narrative writing piece. At these lunch sessions, we worked to increase the elaboration in his weekly story, and to grow his craft in areas like character creation, dialogue, passive voice, and modified structure. My descriptive feedback, which connected directly to his writing, allowed Matt to be successful.

As we continued to work on the assignment in class, I would gently encourage him to name the skills we worked on at lunch, and remind him to make use of them.

After several weeks, Matt, smiling, announced that he got a 4 (a mark of excellent achievement)—because he worked to get it. He wasn’t bragging, though, when he said this to our class. He was encouraging others to put in some work to grow their achievement. I smiled.

From these experiences, I’ve learned a few things as a teacher:

- Students are honest evaluators of their own work.

- Students will strive to meet expectations you set when they trust that you care about them and their work.

- Student can gain confidence through achievement on meaningful tasks.

It’s important to allow kids to do their best, even when the methods to achieve this may look different.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.

For the next two years, I will be part of the

For the next two years, I will be part of the