During the second half of the school year, I opened my classroom up to a doctoral student from the University of Michigan who was studying what untaught and sometimes intangible things make teachers successful. It was a wonderful experience, and I learned a lot about myself as a teacher through the reflective nature of the process. As compensation for my time and energy, I was presented with a $100 gift card for Amazon. I knew exactly what I would buy: books! One book, in particular, was on my wish list, Jennifer Serravallo’s The Reading Strategies Book. I had seen the publisher, Heinemann, promoting it on Twitter, and it looked really useful and practical for teachers on a day to day basis.

During the second half of the school year, I opened my classroom up to a doctoral student from the University of Michigan who was studying what untaught and sometimes intangible things make teachers successful. It was a wonderful experience, and I learned a lot about myself as a teacher through the reflective nature of the process. As compensation for my time and energy, I was presented with a $100 gift card for Amazon. I knew exactly what I would buy: books! One book, in particular, was on my wish list, Jennifer Serravallo’s The Reading Strategies Book. I had seen the publisher, Heinemann, promoting it on Twitter, and it looked really useful and practical for teachers on a day to day basis.

The book arrived in early June, and I set it aside to look at once the school year ended. In mid-June, I was a presenter in the 6-8 Informational Reading & Writing strand at the MiELA Network Institute. I hadn’t yet looked through The Reading Strategies Book, but I threw it into my crate just in case I got some extra time. My co-presenter, Cory Snider (@sniderc), and I wanted to be especially mindful of the needs of our participants since a number of them were returning from the year prior. So as we were looking through the exit comments at the end of day two and thinking about our plans for day three, I grabbed The Reading Strategies Book out of my crate and started skimming it.

Based on the reviews I had seen, I had a hunch the book was going to be good, but I didn’t know just how good it would be. As Cory was busy trying to put the finishing touches on our presentation for the next day, I kept yelling, “Cory! Look at this one! It’s perfect!” or “Cory! Isn’t this just the best idea?!” While he did agree that the book seemed pretty great, I think he probably could have done without my outbursts every 30 seconds. We ended up incorporating a number of Serravallo’s strategies into our plans for the next day, and the participants were just as excited as we were about the potential of this book. One group of participants is even planning to use it in their PLC’s next book study based on our recommendation.

The beauty of The Reading Strategies Book is in its simplicity, consistency, and organization. The 300 (!) strategies are broken up by goal, which mimic goals that we might have as teachers as we help students navigate various text types. These goals range from support for early readers to comprehending fiction in a variety of ways to improving comprehension of nonfiction to deepening students’ speaking and listening skills. Serravallo has organized her book so that each strategy fits onto one page, which includes:

- a description of the strategy itself

- a teaching tip or the language she might use in a lesson

- prompts to use when talking with students

- an image that shows an anchor chart or sample student work (I found these especially useful in helping me visualize what a strategy actually looks like in a classroom)

- a suggested level, based on the Fountas and Pinnell Text Level Gradient (I can see teachers adapting them up or down to fit the needs to various students at various levels)

- the genre or text type with which to use the strategy

- the skill the strategy helps develop

- a citation if the strategy came from somewhere else

I have so many pages bookmarked, especially in the nonfiction sections. I anticipate using this book regularly, and I’ve already told a number of my colleagues about it. A science teacher in my building even saw a tweet I made about it and wants to see how it can help her support her students’ understanding of science texts.

Jianna Taylor (@JiannaTaylor) is an ELA and Title 1 teacher at Orchard Lake Middle School in West Bloomfield. She is a member of the AVID Site Team and Continuous School Improvement Team at her school, among other things. She is also a MiELA Network Summer Institute facilitator and member of the OWP Core Leadership Team. Jianna earned her bachelor’s degree from Oakland University and her master’s degree from the University of Michigan. She also writes reviews of children’s books and young adult novels for the magazine Library Media Connection.

Jianna Taylor (@JiannaTaylor) is an ELA and Title 1 teacher at Orchard Lake Middle School in West Bloomfield. She is a member of the AVID Site Team and Continuous School Improvement Team at her school, among other things. She is also a MiELA Network Summer Institute facilitator and member of the OWP Core Leadership Team. Jianna earned her bachelor’s degree from Oakland University and her master’s degree from the University of Michigan. She also writes reviews of children’s books and young adult novels for the magazine Library Media Connection.

Anyone who knows me knows that I am a voracious reader (comes with the English teacher territory, right?). Anyone who knows me really well knows that I’m not just reading books for pleasure, but that I’m a voracious reader of professional books. Case in point: I read five books about grading last summer. Riveting stuff.

Anyone who knows me knows that I am a voracious reader (comes with the English teacher territory, right?). Anyone who knows me really well knows that I’m not just reading books for pleasure, but that I’m a voracious reader of professional books. Case in point: I read five books about grading last summer. Riveting stuff. Upstanders

Upstanders

The writer’s notebook is almost a sacred, mythical element of the writer’s workshop. It is where students’ writing lives take shape and are documented over the course of a year. In my classroom, the writer’s notebook held everything, and I mean EVERYTHING. Any paper I handed out was immediately taped or glued into the notebook, even if it had to be turned on its side or folded over two times. The writer’s notebook was our textbook. So when I heard each one of my students would be getting a Chromebook, I was excited about the possibilities and what that could mean for student writing. But what nagged at me was the loss of the traditional, tangible writer’s notebook.

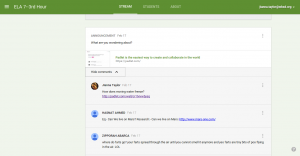

The writer’s notebook is almost a sacred, mythical element of the writer’s workshop. It is where students’ writing lives take shape and are documented over the course of a year. In my classroom, the writer’s notebook held everything, and I mean EVERYTHING. Any paper I handed out was immediately taped or glued into the notebook, even if it had to be turned on its side or folded over two times. The writer’s notebook was our textbook. So when I heard each one of my students would be getting a Chromebook, I was excited about the possibilities and what that could mean for student writing. But what nagged at me was the loss of the traditional, tangible writer’s notebook. Instead of kids bringing their notebooks to one another and reluctantly allowing a partner to write on their prized draft, kids are sharing documents with one another and setting the editing level based on their comfort, with many choosing to only allow their partners to comment on a document. They no longer have to worry that someone is going to “mess up” their paper. They can simply focus on the comments, and especially relish hitting the “Resolve” button when they have revised something. I think it’s more than just reading the comments and making changes, though; kids are having conversations via their comments about writing as well as having conversations about their writing out loud. The conversations about writing are multilayered. If you’ve ever seen a teen text and talk to someone at the same time, you know that holding multiple conversations on various platforms is a way of life. And students also seem to be more responsive to my suggestions because my comments don’t physically change their writing; they are seen as just that: comments and suggestions.

Instead of kids bringing their notebooks to one another and reluctantly allowing a partner to write on their prized draft, kids are sharing documents with one another and setting the editing level based on their comfort, with many choosing to only allow their partners to comment on a document. They no longer have to worry that someone is going to “mess up” their paper. They can simply focus on the comments, and especially relish hitting the “Resolve” button when they have revised something. I think it’s more than just reading the comments and making changes, though; kids are having conversations via their comments about writing as well as having conversations about their writing out loud. The conversations about writing are multilayered. If you’ve ever seen a teen text and talk to someone at the same time, you know that holding multiple conversations on various platforms is a way of life. And students also seem to be more responsive to my suggestions because my comments don’t physically change their writing; they are seen as just that: comments and suggestions.  I had toyed with the idea of having students use a single, running Google Doc to keep a notebook, but that doesn’t work as easily as a traditional notebook does, especially when using Google Classroom, because some of the documents would be in Classroom and some would be in the running Google Doc. I thought toggling between the two would be difficult. Obviously, no single platform seems to be perfect (it’s unlikely that anything will ever meet every need/want). Despite the misgivings I may have, my students do not seem to be having the same internal struggles that I am having. Using their Chromebooks has quickly become second nature, with the biggest complaint being that the WiFi isn’t working quickly enough!

I had toyed with the idea of having students use a single, running Google Doc to keep a notebook, but that doesn’t work as easily as a traditional notebook does, especially when using Google Classroom, because some of the documents would be in Classroom and some would be in the running Google Doc. I thought toggling between the two would be difficult. Obviously, no single platform seems to be perfect (it’s unlikely that anything will ever meet every need/want). Despite the misgivings I may have, my students do not seem to be having the same internal struggles that I am having. Using their Chromebooks has quickly become second nature, with the biggest complaint being that the WiFi isn’t working quickly enough!