After writing last month about giving my students a “free day,” I began to contemplate the end of the year. It is always such a crazy time: special events, end-of-year celebrations, and unexpected happenings inevitably interrupt instruction so that anything we are doing does not seem to be done well. Students lose their enthusiasm and often their ability to focus.

After writing last month about giving my students a “free day,” I began to contemplate the end of the year. It is always such a crazy time: special events, end-of-year celebrations, and unexpected happenings inevitably interrupt instruction so that anything we are doing does not seem to be done well. Students lose their enthusiasm and often their ability to focus.

To counter this trend, I decided to try to harness the excitement of the free day and allow my students to design their own end-of-the year reading and writing project.

Taking a Leap

I told my students what I was thinking: you design a purposeful reading and writing project for the end of the year. You may work alone, with a partner, or in a group. Each project must contain a reading and writing component. If you are using mentor texts, you have to write at least a paragraph explaining how the text helped you with your writing. You also have to design a rubric, using previous class rubrics as a model. Finally, if you can’t come up with anything, I will assign you a text I think you’ll love, and you can read it and write a literary essay about it.

We brainstormed lots of options on the board and then they had time to think. I have to say, I was a bit nervous, but so far I’ve been pleasantly surprised and, in some cases, astounded.

I’ve had parents tell me that their children have come home saying this is going to be the best end of the year ever. They are excited about their projects and are taking ownership of their learning. Every day they come in ready to get to work, asking me about new aspects of projects, and digging for more information. There is energy and excitement in the room . . . in late May. Wow.

Project Ideas

The best ideas are coming from the students, of course.

One of my favorites comes from three girls who are working on writing fantasy. Two of the girls have been working for a while on a book outside of class. They wanted to bring in the third girl and decided that she would write a companion text, creating biographies of the characters and maps of the worlds in which they live.

Two other students are working on a poetry anthology, analyzing mentor texts and trying copy changes–all the way down to abstract concepts and syllabication. Students are creating board games, informational picture books, and websites. It is a bit chaotic, but totally worth it.

Two other students are working on a poetry anthology, analyzing mentor texts and trying copy changes–all the way down to abstract concepts and syllabication. Students are creating board games, informational picture books, and websites. It is a bit chaotic, but totally worth it.

Capturing the Power

I want this kind of excitement and energy all year in my classroom. But how? How do I meet the needs of my learners, deliver the required curriculum, and have the same level of student engagement? I’ve learned a little about Project Based Learning, which seems to fit, but I need to learn more.

This will be the question that sits in my mind all summer as I read and plan for next year. Rather than the best “end of school ever,” I want every year in my classroom to feel like the best learning ever. I suppose that is the never-ending quest of all teachers. Right now, I’m going to enjoy these last few weeks as I watch the thinking and learning in action, and allow this to inspire me for the future.

Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for Clarkston Community Schools, where she has been teaching full time since 2006. She is blessed to teach Language Arts and Social Studies for her class and her teaching partner’s class, while her partner teaches all of their math and science. This enables them to focus on their passions and do the best they can for kids. Beth was chosen as Teacher of the Year for 2013-2014 in her district. She earned a B.S. in Education at Kent State University and a Master’s in Educational Technology at Michigan State University.

Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for Clarkston Community Schools, where she has been teaching full time since 2006. She is blessed to teach Language Arts and Social Studies for her class and her teaching partner’s class, while her partner teaches all of their math and science. This enables them to focus on their passions and do the best they can for kids. Beth was chosen as Teacher of the Year for 2013-2014 in her district. She earned a B.S. in Education at Kent State University and a Master’s in Educational Technology at Michigan State University.

“Just give me a topic. I’ll write about anything. I don’t care.”

“Just give me a topic. I’ll write about anything. I don’t care.”

When May comes, and the green starts to overtake the landscape, and the

When May comes, and the green starts to overtake the landscape, and the  I would have the students keep the envelopes open, so that I could “grade” them and also screen for any letter of bad intent (only one or two in the many years did this, but I’m glad I checked in the end).

I would have the students keep the envelopes open, so that I could “grade” them and also screen for any letter of bad intent (only one or two in the many years did this, but I’m glad I checked in the end). Caroline Thompson (

Caroline Thompson (

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a  At my school, we had a reading goal of 20 books a year for each student. This goal was further broken down into page goals for grade levels — 400 pages each month for 6th graders, 500 for 7th graders, and 600 for 8th graders.

At my school, we had a reading goal of 20 books a year for each student. This goal was further broken down into page goals for grade levels — 400 pages each month for 6th graders, 500 for 7th graders, and 600 for 8th graders. As we continued, for many it was easy to double the two-week goal. For others who struggled to meet their goals, the common theme was that they didn’t make time to read daily. So we used a daily reading log, a visual tool that allowed students to see their amount of reading.

As we continued, for many it was easy to double the two-week goal. For others who struggled to meet their goals, the common theme was that they didn’t make time to read daily. So we used a daily reading log, a visual tool that allowed students to see their amount of reading. Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the  Back in January an article came out that had the teachers in my building thinking, We’ve been saying that forever and finally someone is acting on it! The article was titled

Back in January an article came out that had the teachers in my building thinking, We’ve been saying that forever and finally someone is acting on it! The article was titled  I am fortunate that in my district, when we started the all-day, every-day kindergarten program in 2008, the district stressed the importance of play in the classroom. I am also fortunate that my building principal supports this. We have free-choice play in my classroom every day; this is something that never changes and I hope never will.

I am fortunate that in my district, when we started the all-day, every-day kindergarten program in 2008, the district stressed the importance of play in the classroom. I am also fortunate that my building principal supports this. We have free-choice play in my classroom every day; this is something that never changes and I hope never will. Tricia Ziegler (Twitter:

Tricia Ziegler (Twitter:  A funny thing happened as my students were wrapping up their narrative journalism papers a couple weeks ago on the shiny new Chromebooks I’d reserved for the assignment. As I was reviewing a few formatting details with them, it suddenly dawned on me that my deadline for a hard copy of the paper–the end of the hour–was physically impossible. There is no printer attached to our Chromebook carts.

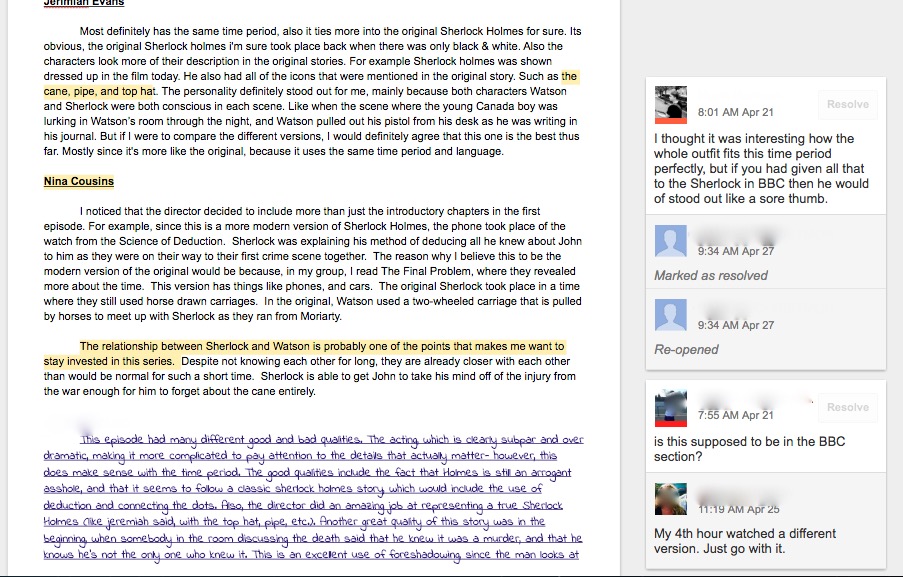

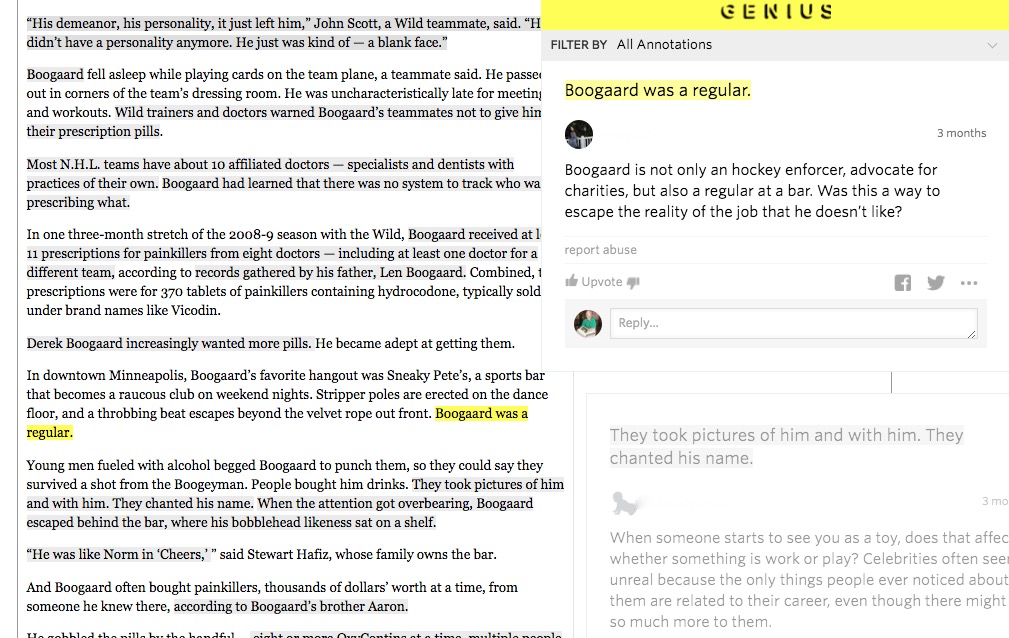

A funny thing happened as my students were wrapping up their narrative journalism papers a couple weeks ago on the shiny new Chromebooks I’d reserved for the assignment. As I was reviewing a few formatting details with them, it suddenly dawned on me that my deadline for a hard copy of the paper–the end of the hour–was physically impossible. There is no printer attached to our Chromebook carts. Let’s consider briefly what written feedback tends to look like when you have 100 essays to grade.

Let’s consider briefly what written feedback tends to look like when you have 100 essays to grade.

It’s that time of year here in Michigan: the dreaded standardized testing window we now call M-STEP. My 5th graders just endured five days of this testing over a two-week period. The first two days were ELA tests–hours of online reading and writing. Needless to say, after the second afternoon my kiddos were in need of a break.

It’s that time of year here in Michigan: the dreaded standardized testing window we now call M-STEP. My 5th graders just endured five days of this testing over a two-week period. The first two days were ELA tests–hours of online reading and writing. Needless to say, after the second afternoon my kiddos were in need of a break. This day really got me thinking about workshop and curriculum. We power through what we need to teach: mini lessons, teaching points, big ideas. We give kids lots of independent practice within the unit we are teaching.

This day really got me thinking about workshop and curriculum. We power through what we need to teach: mini lessons, teaching points, big ideas. We give kids lots of independent practice within the unit we are teaching.