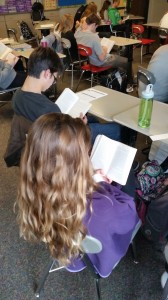

We’ve reached the point in my 8th grade classroom where we’ve modeled, practiced, and established norms that we can use in our workshop classroom. Additionally, I have also conferenced with each student to give them a next step as they continue their reading and writing work. This, however, is not a blog post about effective conferencing, rather it’s about what I’ve learned from conferencing with a particular student. This experience leaves me wondering whether we, as teachers, always realize the effects we have on students?

We’ve reached the point in my 8th grade classroom where we’ve modeled, practiced, and established norms that we can use in our workshop classroom. Additionally, I have also conferenced with each student to give them a next step as they continue their reading and writing work. This, however, is not a blog post about effective conferencing, rather it’s about what I’ve learned from conferencing with a particular student. This experience leaves me wondering whether we, as teachers, always realize the effects we have on students?

Kyle sat down to conference with me about his writing. He particularly wanted to discuss one of his poems from the 8th grade CCSS/MAISA Launching Writer’s Workshop unit that focuses on narrative poetry. Anxiety radiated off of him as he explained that he had written nothing that he felt was valuable. With his permission, I looked at his writer’s notebook, and a theme became clear in his writing. He was writing what he thought I wanted. His notebook had seed ideas that mirrored my own modeled topics as well as imitations that stayed in the structure and topic of the original text. I praised Kyle for all of his good work in practicing all of our new class skills. Then, I broke down his next steps for him.

It was apparent that Kyle needed smaller steps than even the workshop curriculum daily sessions offered. So we began with: what story do you want to tell? And later, we discussed: what will be the beginning, middle, and end of that story? Then he was able to write a narrative poem draft. After peer review, he came to me and said that he thought his poem was too long (about 3 handwritten pages). So, again, step-by-step we worked on his poem with ideas like cutting out any repeating words or phrases and details that did not suit his beginning, middle, and end planning. The next day, he came running in to show me that he had cut his poem down to about one page, and he was very happy to tell me that this draft was much better than the previous one.

Amidst these in-class conferences with Kyle, I met Kyle’s mom. She shared a story with me about a 3rd grade teacher who told Kyle that he was not a writer. While I’m not writing this post to place blame, I see that when Kyle sits down to write, he does so with doubt. This doubt may have come from the seed planted by that teacher, but it probably also came from many other writing experiences that perhaps didn’t go as Kyle had hoped. In the end, Kyle had a very successful first writing unit in my classroom, and I hope that he’ll continue to feel excited about writing as we get into argument and informative writing. But this whole episode left me wondering–what effects do we, as teachers, have on students?

Amidst these in-class conferences with Kyle, I met Kyle’s mom. She shared a story with me about a 3rd grade teacher who told Kyle that he was not a writer. While I’m not writing this post to place blame, I see that when Kyle sits down to write, he does so with doubt. This doubt may have come from the seed planted by that teacher, but it probably also came from many other writing experiences that perhaps didn’t go as Kyle had hoped. In the end, Kyle had a very successful first writing unit in my classroom, and I hope that he’ll continue to feel excited about writing as we get into argument and informative writing. But this whole episode left me wondering–what effects do we, as teachers, have on students?

This experience with Kyle reminded me of a particularly bad writing experience I had with a college English professor my first semester. The short version is that he told me I couldn’t write and that I could not major in English. This negative experience my first semester was coupled with an excellent grade on a paper in a class taught by a published author. He told me that I had wonderful written ideas and a great depth of thought. I later worked for this professor and even helped him review one of his manuscripts for publication. I am thankful today that these experiences happened in the same semester because I’m not sure I could have moved past the negative professor’s comments. Instead, I decided to work to become a stronger writer. While this work is never over, I feel that I have become a strong writer. I also hope that I’ve given my students the confidence to be successful, independent writers. So, each day I have to consider that the things we say to our students affect them. What conversations will you have with students today?

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.

We have a few more details about the tests that will be given in the spring, including types of tests at each grade level. A batch of sample items is in production now. This sample will be available “shortly” to all schools and will demonstrate the online functions and tools of the M-STEP.

We have a few more details about the tests that will be given in the spring, including types of tests at each grade level. A batch of sample items is in production now. This sample will be available “shortly” to all schools and will demonstrate the online functions and tools of the M-STEP.

This experience showed me and Doug that it is imperative for disciplines to collaborate. Neither of us could have gotten the quality of work the students produced had we done this separately. For the first time, students were seeing exactly how the skills they learn in their individual classes apply to all classes. They were developing skills–research skills, presentation skills– not just memorizing facts and figures.

This experience showed me and Doug that it is imperative for disciplines to collaborate. Neither of us could have gotten the quality of work the students produced had we done this separately. For the first time, students were seeing exactly how the skills they learn in their individual classes apply to all classes. They were developing skills–research skills, presentation skills– not just memorizing facts and figures. Lisa Kraiza teachers eighth grade English Language Arts at Oak Park Preparatory Academy. She is also a member of the Core Leadership Team of the

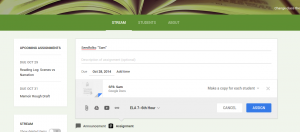

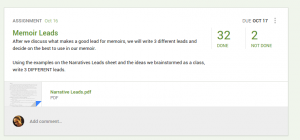

Lisa Kraiza teachers eighth grade English Language Arts at Oak Park Preparatory Academy. She is also a member of the Core Leadership Team of the  At the end of last year, we found out that our district, West Bloomfield, would be going

At the end of last year, we found out that our district, West Bloomfield, would be going

ianna Taylor is an ELA and Title 1 teacher at Orchard Lake Middle School in West Bloomfield. She is a member of the AVID Site Team and Continuous School Improvement Team at her school, among other things. She is also a

ianna Taylor is an ELA and Title 1 teacher at Orchard Lake Middle School in West Bloomfield. She is a member of the AVID Site Team and Continuous School Improvement Team at her school, among other things. She is also a

Hattie Maguire is an English teacher and Content Area Leader at Novi High School. She is spending her fourteenth year in the classroom teaching AP English Language and Composition, English 10, Debate, and Practical Public Speaking. She is a National Board Certified Teacher who earned her BS in English and MA in Curriculum and Teaching from Michigan State University.

Hattie Maguire is an English teacher and Content Area Leader at Novi High School. She is spending her fourteenth year in the classroom teaching AP English Language and Composition, English 10, Debate, and Practical Public Speaking. She is a National Board Certified Teacher who earned her BS in English and MA in Curriculum and Teaching from Michigan State University. Recognize and acknowledge students’ difficulty and the effort. “I know this is hard, and I can see you’re…” It’s unnatural and hard to go from being an excellent talker to being a deliberate writer. Putting myself in the role of learner reminded me of that.

Recognize and acknowledge students’ difficulty and the effort. “I know this is hard, and I can see you’re…” It’s unnatural and hard to go from being an excellent talker to being a deliberate writer. Putting myself in the role of learner reminded me of that. Never forget your audience. Like much of what I learned, this applies to students and teachers. It’s all about moving your audience. This goes for writers, actors and teachers. I think of those long-winded professors I had in college. Droning on, oblivious to the blanks stares, they might as well have been talking to a mirror. (Any teacher who thinks that a lecture is a good way to teach should be forced to actually sit through one.) It’s not about the director, or the actor, or the writer. It’s about getting that audience where they need to be. As a teacher, I think about the purpose–where I want to be–but I try to listen to my audience; find out what works for them and use that to reach the purpose.

Never forget your audience. Like much of what I learned, this applies to students and teachers. It’s all about moving your audience. This goes for writers, actors and teachers. I think of those long-winded professors I had in college. Droning on, oblivious to the blanks stares, they might as well have been talking to a mirror. (Any teacher who thinks that a lecture is a good way to teach should be forced to actually sit through one.) It’s not about the director, or the actor, or the writer. It’s about getting that audience where they need to be. As a teacher, I think about the purpose–where I want to be–but I try to listen to my audience; find out what works for them and use that to reach the purpose. Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a