Sometimes, the teaching pieces all come together beautifully, like different musicians in a carefully rehearsed symphony. You plan something that dovetails perfectly with something else, which builds to something better, and on and on, to the amazing crescendo of learning.

Sometimes, the teaching pieces all come together beautifully, like different musicians in a carefully rehearsed symphony. You plan something that dovetails perfectly with something else, which builds to something better, and on and on, to the amazing crescendo of learning.

At least that’s what happens in my dreams.

Instead of a symphony, I have more of a garage-band vibe going in my room this year. We try something that isn’t quite right, which leads to something a little bit better, and on and on, to a quirky song that’s kinda cool but also not radio-ready.

These days, my quirky song is the work I’ve been doing with explicit grammar instruction and cross-curricular writing, and this past week I finally felt like we were getting somewhere.

The Looming Exam

Going into the week, I had two competing goals. First, I wanted students to hone their revision skills and provide some good feedback for our partner Physics class, which I wrote about last month. Second, I needed to get them moving on their review for the AP Language exam, which is about two and a half weeks away (insert emojis of horror here).

Like it or not–sorry, Physics kids–my students are most concerned with their AP exam. As I was planning this week, I was regretting telling Brian, the Physics teacher, we’d still bring our classes together. I was starting to worry that, though this exercise was really interesting to me and helpful for Brian and his kids, the joint work was not incredibly relevant for my kids at this critical point in their AP Language course.

Then I attended the Oakland Schools webinar with Connie Weaver, which focused on her book Grammar to Enrich and Enhance Writing.

All the pieces fell together.

Learning with Revision

Dr. Weaver helped me see how easily my two competing goals for the week weren’t competing at all.

In her webinar, Dr. Weaver focused on revision with argumentative writing, and she used a sample essay from the new SAT as her model. She walked us through adding things–participial phrases, appositives, absolutes–or reworking existing sentences to include more complex structures. I had been asking my students to mimic the writing they were seeing in mentor texts, to write with those things in mind, but I hadn’t asked them to explicitly go back and revise or add to their writing using those tools.

In her webinar, Dr. Weaver focused on revision with argumentative writing, and she used a sample essay from the new SAT as her model. She walked us through adding things–participial phrases, appositives, absolutes–or reworking existing sentences to include more complex structures. I had been asking my students to mimic the writing they were seeing in mentor texts, to write with those things in mind, but I hadn’t asked them to explicitly go back and revise or add to their writing using those tools.

The next week, I shamelessly stole Dr. Weaver’s activity from the webinar and adapted it to work with my students. We did a quick refresh of grammatical structures, and then practiced revising small chunks of a sample student essay. I discovered quickly that our work with mentor texts had been successful; my students can identify good writing.

The second part of the activity, though, was much more telling. I had my students revise text on a shared Google Doc, which allowed us to all see the different options. This led to some great discussions about active vs. passive voice, the use of participial phrases to add detail, and the use of appositives to surprise readers.

Suddenly, these grammatical terms were starting to mean something to my students and their writing. Asking students to identify grammatical structures is one thing; forcing them to take an existing sentence and apply said structure is totally different.

They weren’t always successful–some were wildly unsuccessful–but now they were applying these grammatical terms to real student writing. Before, by only identifying techniques and asking students to mimic them, I think I was inadvertently implying that good writing happens naturally the first time. Sometimes it does, but this gave students some specific tools to use when it doesn’t.

Applying the Lessons

Wednesday and Thursday, we unleashed our newly honed revision skills on the Physics essays. I modeled giving feedback on one essay: general comments regarding organization and evidence, and three specific suggestions for making the writing more sophisticated. I asked students to find sentences they could revise, and to then give advice about how to replicate those revisions later in the essay. Instead of just seeing all the things that were “wrong” with the essays, they started seeing the possibilities.

On Friday we will take the final step: their own essays. On Tuesday night after school, they all sat for a full-length practice AP exam–three essays in two hours. Timed writing doesn’t allow for careful, thoughtful revision, but on Friday we will look for the possibilities in those essays and practice careful revision.

At the end of this week, we’re definitely still going to be a quirky garage band. But we’re going to be a few steps closer to our big break, I think.

Hattie Maguire is an English teacher and Content Area Leader at Novi High School. She is spending her fifteenth year in the classroom teaching AP English Language and Composition and English 10. She is a National Board Certified Teacher who earned her BS in English and MA in Curriculum and Teaching from Michigan State University.

Hattie Maguire is an English teacher and Content Area Leader at Novi High School. She is spending her fifteenth year in the classroom teaching AP English Language and Composition and English 10. She is a National Board Certified Teacher who earned her BS in English and MA in Curriculum and Teaching from Michigan State University.

Dylan Wiliam is a world-renowned educational leader and researcher, specializing in teacher development and formative assessment. On today’s podcast, Dylan shares the key aspects of formative assessment. He offers his thoughts on teacher development. And he shares some practical ideas to consider for your teaching.

Dylan Wiliam is a world-renowned educational leader and researcher, specializing in teacher development and formative assessment. On today’s podcast, Dylan shares the key aspects of formative assessment. He offers his thoughts on teacher development. And he shares some practical ideas to consider for your teaching.

In July 2016, Oakland Schools had a significant reorganization. During this reorganization, smaller units were formed from the existing larger departments, and some additional administrative roles were created. A number of these units are part of the District and School Services. Dr. Heidi Kattula is the Executive Director of District and School Services at Oakland Schools.

In July 2016, Oakland Schools had a significant reorganization. During this reorganization, smaller units were formed from the existing larger departments, and some additional administrative roles were created. A number of these units are part of the District and School Services. Dr. Heidi Kattula is the Executive Director of District and School Services at Oakland Schools. The best professional development has to inspire me, engage me, and challenge me to try something new. Some of my favorite conferences have been

The best professional development has to inspire me, engage me, and challenge me to try something new. Some of my favorite conferences have been  Come Hangout!

Come Hangout! Caroline Thompson (

Caroline Thompson (

Jianna Taylor (

Jianna Taylor ( Sometimes, the teaching pieces all come together beautifully, like different musicians in a carefully rehearsed symphony. You plan something that dovetails perfectly with something else, which builds to something better, and on and on, to the amazing crescendo of learning.

Sometimes, the teaching pieces all come together beautifully, like different musicians in a carefully rehearsed symphony. You plan something that dovetails perfectly with something else, which builds to something better, and on and on, to the amazing crescendo of learning. In her webinar, Dr. Weaver focused on

In her webinar, Dr. Weaver focused on

Like most teachers in Michigan, last week I spent two days proctoring the state’s SAT and ACT Work Keys tests. I collected the box of tests, read from the script, made sure there were no errant marks, and was generally absolutely bored.

Like most teachers in Michigan, last week I spent two days proctoring the state’s SAT and ACT Work Keys tests. I collected the box of tests, read from the script, made sure there were no errant marks, and was generally absolutely bored.  My earliest “hacks” came when I moved the focus away from the teacher, me, as the primary audience for students’ writing, and

My earliest “hacks” came when I moved the focus away from the teacher, me, as the primary audience for students’ writing, and  Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a  I think it’s safe to say that there’s a bit more mathematical calculation in your normal English classroom pedagogy than there was, say, five years ago.

I think it’s safe to say that there’s a bit more mathematical calculation in your normal English classroom pedagogy than there was, say, five years ago.  The funny thing about data, though, is that numbers aren’t as clear and objective as all those charts and bar graphs would have us believe. If you don’t want to take an English teacher’s word for that, get ahold of Nate Silver’s

The funny thing about data, though, is that numbers aren’t as clear and objective as all those charts and bar graphs would have us believe. If you don’t want to take an English teacher’s word for that, get ahold of Nate Silver’s

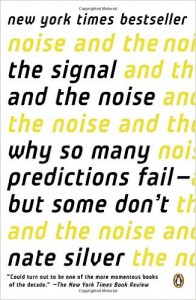

Recently, I facilitated a webinar about preparing students for the ELA M-STEP. (You can access a

Recently, I facilitated a webinar about preparing students for the ELA M-STEP. (You can access a

At the start of December, I attended a workshop at the Detroit Port Authority Lofts, which, it turns out, is an event space, not a place where ships check in. I’ve lived in southeast Michigan my entire life, and spent many, many hours in the city. But I didn’t know this place was there. I thought, The city of Detroit is like teachers: there’s so much good stuff happening, but no one knows about it, or the ones who do know treat the information like it’s secret.

At the start of December, I attended a workshop at the Detroit Port Authority Lofts, which, it turns out, is an event space, not a place where ships check in. I’ve lived in southeast Michigan my entire life, and spent many, many hours in the city. But I didn’t know this place was there. I thought, The city of Detroit is like teachers: there’s so much good stuff happening, but no one knows about it, or the ones who do know treat the information like it’s secret.

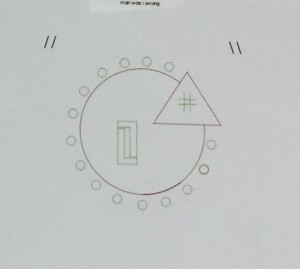

were learning about conics. With that, they created logos for us to vote on. Most of my department picked the logo shown on the right. It reflected our desire to have a design that opened a conversation, by provoking a person to ask about the logo. The shapes are meant to represent aspects of our discipline and practice. We didn’t want books or pens or apples. Too

were learning about conics. With that, they created logos for us to vote on. Most of my department picked the logo shown on the right. It reflected our desire to have a design that opened a conversation, by provoking a person to ask about the logo. The shapes are meant to represent aspects of our discipline and practice. We didn’t want books or pens or apples. Too  Recently I had the pleasure to conduct professional learning sessions on literacy with three separate groups of teachers. The teachers spanned every discipline, which is understandable, given the trends in education throughout the country.

Recently I had the pleasure to conduct professional learning sessions on literacy with three separate groups of teachers. The teachers spanned every discipline, which is understandable, given the trends in education throughout the country.

Rick Joseph is a National Board Certified Teacher and has taught 5/6 grade at Covington School in the Birmingham Public School district since 2003. Prior, he served as a bilingual educator and trainer for nine years in the Chicago Public Schools. Rick is thrilled to serve as the 2016 Michigan Teacher of the Year. Through Superhero Training Academy, Rick’s students have created a superhero identity to uplift the communities where they learn and live.

Rick Joseph is a National Board Certified Teacher and has taught 5/6 grade at Covington School in the Birmingham Public School district since 2003. Prior, he served as a bilingual educator and trainer for nine years in the Chicago Public Schools. Rick is thrilled to serve as the 2016 Michigan Teacher of the Year. Through Superhero Training Academy, Rick’s students have created a superhero identity to uplift the communities where they learn and live.