James was spread out on one of the counters, with all his papers and materials circling his laptop. He smiled as I approached.

James was spread out on one of the counters, with all his papers and materials circling his laptop. He smiled as I approached.

“So I heard you are starting over,” I said.

“Yeah. I found stronger evidence for this prompt,” James said. (The student’s name has been changed for the sake of this post.)

“That’s really thoughtful of you. Great writing move!”

We talked through his planning ideas and how he was going to use his evidence, and he shared with me some specific examples of how in his bioethics essay he would defend the use of GMOs.

After we were ready to wrap up our conference, I remarked, “You know, I don’t think you really are going to need our support much this semester.”

Moving Beyond Support

As an MTSS interventionist, it can be challenging to know when a writer is ready to move past support. This year, I was hired by my district to coordinate academic interventions for students whose data reveal that they have a skills deficit. In particular, I work closely with Tier Two and Tier Three students to develop content literacy skills. I began working with James a month into the school year, coordinating support in his U.S. History class, then his Biology class.

With James, I observed his growing independence when he showed me that he was thinking carefully about his writing. When writers are given opportunity to talk about their writing, it allows for us to assess what they need most to move forward. And since I only see my students periodically for support in and out of their classes, it’s these conversations that drive everything I do to support a developing writer.

So what do I look for most in a writer when I am deciding to pull back support? Intentional thought and active engagement. Does it mean that students won’t need an occasional conference to lead them to clearer drafts or prompt them to consider new ideas? Absolutely not. But when writers can explain their process, explain their thinking, and explain why their choices matter, it’s time to let go. The best writing lessons are born out of risk, and students won’t take those risks if they are waiting for our stamp of approval.

Letting go can be scary, but it need not be abrupt. Building an instructional practice around dialogue allows for gradual reduction of support. Conversation is vital because it helps teachers to identify what kind of support an underperforming writer still needs. Moreover, conversation sniffs out a mismatch between perception and skill, leading the way to targeted feedback and more.

Intentional Positioning

When I told him he didn’t need me, James looked surprised.

“Really?”

A big smile stretched across his face, followed by his quickly agreeing. James knew he was ready too, but he needed an affirmation.

Years ago when I first began working with resistant and underperforming writers, I came across a theory on positioning. Positioning theory supports the idea that social interactions create identities, and these identities are fluid. As a result, educators have the power to reposition a student’s identity in negative or positive ways.

When I sat down with James to conference about his biology paper, I saw how his posture changed the moment I remarked that he wouldn’t be needing my support much longer. Our conversation revealed to James that there was a mismatch between how he felt as a writer and his actual skill level. Changing a student’s perception about himself alone can raise achievement in an underperforming student, and intentional positioning is the final and arguably most important phase of the intervention process. Students have to accept the good we see in them.

The final proof that James was ready to move beyond my support occurred when James’ English teacher told me how she watched him independently and proficiently compose a response to Fahrenheit 451. When I told James that his teacher had positive feedback on his writing, he proceeded to tell me his thoughts on Fahrenheit 451, his assigned novel for English 9. We had a brief but rich conversation about Montag’s dysfunctional relationship with his wife, and just how timely the classic dystopian novel is for 2017. Here, giving his voice value positioned James to fully take on the behaviors of a strong reader and writer.

Without prompting, James was independently making meaning and composing on his own. He knew enough to quit an essay that didn’t yield compelling evidence. His genuine responses about a complex text reflected his growth and development as a reader and writer.

And our conversation made clear that it was time for me to let go. So I did.

Lauren Nizol (@CoachNizol) is an MTSS Student Support Coach and Interventionist at Novi High School. She has eleven years of classroom experience, teaching English, IB Theory of Knowledge and English Lab. Lauren completed her undergraduate degree in History, English and Secondary Education at the University of Michigan-Dearborn and her Masters from Eastern Michigan University in English Education. She is a National Writing Project Teacher Consultant with the Eastern Michigan Writing Project and an advocate for underperforming students and literacy interventions.

Lauren Nizol (@CoachNizol) is an MTSS Student Support Coach and Interventionist at Novi High School. She has eleven years of classroom experience, teaching English, IB Theory of Knowledge and English Lab. Lauren completed her undergraduate degree in History, English and Secondary Education at the University of Michigan-Dearborn and her Masters from Eastern Michigan University in English Education. She is a National Writing Project Teacher Consultant with the Eastern Michigan Writing Project and an advocate for underperforming students and literacy interventions.

Dr. Wanda Cook-Robinson is the Superintendent of Oakland Schools. She is an experienced educator with roles that range from classroom teacher to District Superintendent. In 2013, she received Michigan’s Superintendent of the Year award. This year she received the Courage Award for Educational Excellence and Development at the Martin Luther King, Jr., Luncheon.

Dr. Wanda Cook-Robinson is the Superintendent of Oakland Schools. She is an experienced educator with roles that range from classroom teacher to District Superintendent. In 2013, she received Michigan’s Superintendent of the Year award. This year she received the Courage Award for Educational Excellence and Development at the Martin Luther King, Jr., Luncheon.

James was spread out on one of the counters, with all his papers and materials circling his laptop. He smiled as I approached.

James was spread out on one of the counters, with all his papers and materials circling his laptop. He smiled as I approached.  Lauren Nizol (

Lauren Nizol ( As my students work through the

As my students work through the  Not all the conversations go this way. But enough of them do that I take notice. Is my thinking about empathy and how to get it wrong? I’m also worried that some of these students will slip back into “a prove my point/win the argument” mindset, but I am encouraged.

Not all the conversations go this way. But enough of them do that I take notice. Is my thinking about empathy and how to get it wrong? I’m also worried that some of these students will slip back into “a prove my point/win the argument” mindset, but I am encouraged. Rick Kreinbring (

Rick Kreinbring ( I’ve had frequent conversations about contextual pools lately. I hear more and more of my colleagues speaking about the challenges that arise in teaching their subject matter when the contextual pool of the students is so limited. That is, when our students have very little background knowledge on a subject, it is very difficult for them to learn new material or to garner any interest in doing so.

I’ve had frequent conversations about contextual pools lately. I hear more and more of my colleagues speaking about the challenges that arise in teaching their subject matter when the contextual pool of the students is so limited. That is, when our students have very little background knowledge on a subject, it is very difficult for them to learn new material or to garner any interest in doing so. Bethany Bratney

Bethany Bratney I’m having a really hard time with the fact that I will not be in the same place as my daughter when she is in preschool, even though I know that parents before me have done this. I won’t have a shared experience. I will not be privy to that part of her life.

I’m having a really hard time with the fact that I will not be in the same place as my daughter when she is in preschool, even though I know that parents before me have done this. I won’t have a shared experience. I will not be privy to that part of her life.

Caroline Thompson (

Caroline Thompson ( My youngest daughter is a wonderfully spunky first grader whom people often call “headstrong,” using that tone that suggests they’ll make sure and say a prayer for me later.

My youngest daughter is a wonderfully spunky first grader whom people often call “headstrong,” using that tone that suggests they’ll make sure and say a prayer for me later. There are lots of conversations to be had about this intersection of student interest and assessment. But let’s come back to my daughter for a second. Imagine her ten years from now. Or just look around your own classroom and pick the half dozen or so kids this description fits: She continues to love a good book when someone hands it to her, but she shrinks from most of what a teacher assigns, assuming wearily that it’s more literature that someone else has decided has value–or is being used to test her. If she’s learned to “do school” then she’s compliant but uninterested. If she decides that there are better things to do than complying with assessments, then maybe she’s taking a pass on most of what’s handed to her in an English class.

There are lots of conversations to be had about this intersection of student interest and assessment. But let’s come back to my daughter for a second. Imagine her ten years from now. Or just look around your own classroom and pick the half dozen or so kids this description fits: She continues to love a good book when someone hands it to her, but she shrinks from most of what a teacher assigns, assuming wearily that it’s more literature that someone else has decided has value–or is being used to test her. If she’s learned to “do school” then she’s compliant but uninterested. If she decides that there are better things to do than complying with assessments, then maybe she’s taking a pass on most of what’s handed to her in an English class.

Writing instruction has become my favorite part of teaching, though it didn’t always come easily. In the beginning, my own writing was stilted in structure and lacked voice. I wrote what I had been taught, which was a five paragraph essay and a five sentence paragraph. Not only was my writing boring. The moves I made to create it were not defined enough for students to use as models, except for stilted, formulaic writing that also lacked voice and a sense of ownership.

Writing instruction has become my favorite part of teaching, though it didn’t always come easily. In the beginning, my own writing was stilted in structure and lacked voice. I wrote what I had been taught, which was a five paragraph essay and a five sentence paragraph. Not only was my writing boring. The moves I made to create it were not defined enough for students to use as models, except for stilted, formulaic writing that also lacked voice and a sense of ownership. Amy Gurney (

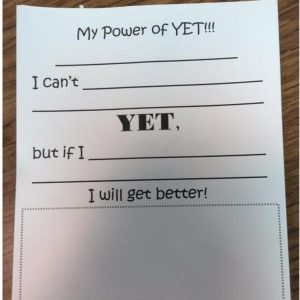

Amy Gurney ( For the past two years, Loon Lake Elementary, where I teach, has really been trying to elicit a growth mindset in our students. We remind them we can always get better at something, and we need to work hard and not give up. We have been focusing on this in cross-grade-level monthly meetings, called Teams, as well as in individual classrooms.

For the past two years, Loon Lake Elementary, where I teach, has really been trying to elicit a growth mindset in our students. We remind them we can always get better at something, and we need to work hard and not give up. We have been focusing on this in cross-grade-level monthly meetings, called Teams, as well as in individual classrooms.

Tricia Ziegler (Twitter:

Tricia Ziegler (Twitter: