As my students work through the Extended Research Argument unit from the National Writing Project, we’re having really good conversations about the issues they’re interested in, and we’re doing a lot of thinking about evidence.

As my students work through the Extended Research Argument unit from the National Writing Project, we’re having really good conversations about the issues they’re interested in, and we’re doing a lot of thinking about evidence.

Most recently, we’ve considered viewpoints that don’t align with our own. We’re at a point where they’ve looked at what is being said about their issues, and are trying to write sympathetic, fair statements that sum up what they’re seeing from people holding different viewpoints.

This is a shift from the way I’ve taught this in the past. Before, of course I taught my students about making concessions and why that’s an important move. The good reason: making a concession shows your reader that you understand the issue’s complexity, and that you’re not a fanatic. The bad reason: The Big Test you’re going to take won’t give you a high score without one.

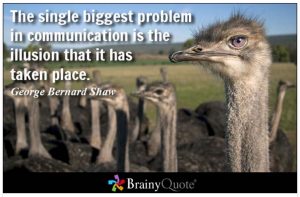

I taught, and maybe thought, about argument as a contest–and so they did too. But what’s coming out of this new work is some real empathy, something I mostly ascribed to fiction reading. I’m thinking that empathy and fairness are traits that are lacking and in need of teaching.

Cultivating Empathy

Fiction maybe lets us experience what another person experiences and feels, but I don’t know a way to require that, or how a student might demonstrate empathy in the kinds of writing we do. Our research-argument project, though, requires it. Students write a statement from the opposing viewpoint that’s fair, and which someone holding that viewpoint would agree with.

Here’s a sample of what all of this has lead us to:

An African-American student, male, tells me his peer reviews don’t think he’s being entirely fair while representing the opposing viewpoint. He writes about police use of force when dealing with communities and individuals of color. He’s not sure he knows how to keep his own bias out of the writing, and how could he?

What’s great about the conversation is that he genuinely wants to be fair because he knows he can make a good argument. He doesn’t want his bias to undermine that. We talk and I read what he’s written. We decide that he’s going to be honest about who he is, and that his next step is to think about whom he wants as his audience.

Whom does he most want to speak to and what might that look like? This young man has little motivation to seek empathy with people who see him as a threat, but because he wants his argument to be taken seriously he’s going to work hard on that empathy piece.

Another young man announced to the class that his issue was raising the minimum wage, because “only losers work for minimum wage–McDonald’s money–and they don’t deserve more.” But now he sits, sharing statements about the opposing viewpoint that contains references to living wages and other topics he hadn’t thought about. His own point of view shows growth and empathy and an understanding of the complexity of his issue. His “only losers” claim is gone, replaced by one that show nuance.

Not all the conversations go this way. But enough of them do that I take notice. Is my thinking about empathy and how to get it wrong? I’m also worried that some of these students will slip back into “a prove my point/win the argument” mindset, but I am encouraged.

Not all the conversations go this way. But enough of them do that I take notice. Is my thinking about empathy and how to get it wrong? I’m also worried that some of these students will slip back into “a prove my point/win the argument” mindset, but I am encouraged.

I sat today and looked through my social media feeds. I didn’t see much empathy, didn’t see anyone trying to sympathetically represent the opposing viewpoint. Is that what we’re up against? A genre that only tries to “win” and never understand?

I thought about my students’ projects. In the last step they are going to produce a piece of civic writing that hopefully achieves their purpose. We’re going to talk about op-eds and petitions, speeches and letters. But I’m afraid that their efforts will get lost in the myopic howling noise of their Twitter feeds and Instagrams and Snapchats. I’m also struggling with how to capture and reward–if that’s the right word–these students for their thinking.

Still it’s a good start.

Right?

Rick Kreinbring (@kreinbring_rick) teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a statewide research project through the Michigan Teachers as Researchers Collaborative partnered with the MSU Writing in Digital Environments Program, which concentrates on improving student writing and peer feedback. Rick has presented at the National Advanced Placement Convention and the National Council of Teachers of English Conference. He is in his twenty-third year of teaching and makes his home in Huntington Woods.

Rick Kreinbring (@kreinbring_rick) teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a statewide research project through the Michigan Teachers as Researchers Collaborative partnered with the MSU Writing in Digital Environments Program, which concentrates on improving student writing and peer feedback. Rick has presented at the National Advanced Placement Convention and the National Council of Teachers of English Conference. He is in his twenty-third year of teaching and makes his home in Huntington Woods.

I’m having a really hard time with the fact that I will not be in the same place as my daughter when she is in preschool, even though I know that parents before me have done this. I won’t have a shared experience. I will not be privy to that part of her life.

I’m having a really hard time with the fact that I will not be in the same place as my daughter when she is in preschool, even though I know that parents before me have done this. I won’t have a shared experience. I will not be privy to that part of her life.

Caroline Thompson (

Caroline Thompson ( Writing instruction has become my favorite part of teaching, though it didn’t always come easily. In the beginning, my own writing was stilted in structure and lacked voice. I wrote what I had been taught, which was a five paragraph essay and a five sentence paragraph. Not only was my writing boring. The moves I made to create it were not defined enough for students to use as models, except for stilted, formulaic writing that also lacked voice and a sense of ownership.

Writing instruction has become my favorite part of teaching, though it didn’t always come easily. In the beginning, my own writing was stilted in structure and lacked voice. I wrote what I had been taught, which was a five paragraph essay and a five sentence paragraph. Not only was my writing boring. The moves I made to create it were not defined enough for students to use as models, except for stilted, formulaic writing that also lacked voice and a sense of ownership. Amy Gurney (

Amy Gurney ( With test prep season beginning and the M-STEP looming, teachers can become frustrated because there are not many

With test prep season beginning and the M-STEP looming, teachers can become frustrated because there are not many

Jianna Taylor (

Jianna Taylor ( Quickly introduced to the intricacies of

Quickly introduced to the intricacies of

The best professional development has to inspire me, engage me, and challenge me to try something new. Some of my favorite conferences have been

The best professional development has to inspire me, engage me, and challenge me to try something new. Some of my favorite conferences have been  Come Hangout!

Come Hangout! Caroline Thompson (

Caroline Thompson ( Last year I participated in a book study at the

Last year I participated in a book study at the  Step 1: Expand Our Horizons

Step 1: Expand Our Horizons