The Alchemist, by Paulo Coelho, was given to me by a colleague, who said that the book is for the journey that our team is on. I had to admit, I had never read the text. It sat on a classroom bookshelf for years. Some students chose it for independent reading, yet I never had a kid use it during a reading unit, so it wasn’t ever on my book stack.

The Alchemist, by Paulo Coelho, was given to me by a colleague, who said that the book is for the journey that our team is on. I had to admit, I had never read the text. It sat on a classroom bookshelf for years. Some students chose it for independent reading, yet I never had a kid use it during a reading unit, so it wasn’t ever on my book stack.

And then, about a year ago, a popular song by Macklemore made some recommendations for life. One of them was, “I recommend that you read The Alchemist / Listen to your teachers, but cheat in Calculus.” I can’t speak to the math recommendation, as a person who avoided Calculus like the plague. But I can recommend that everyone from grade 7 onward read The Alchemist.

The Plot

Santiago is a shepherd who buys his own flock of sheep, even though it isn’t his family’s profession. While looking at his herd and making plans for his future, he meets a man who encourages him to look into his heart. Santiago must look for his true desire, or, as it comes to be known in the book, his “personal legend.”

The decision to achieve his personal legend takes Santiago on a journey. He visits other parts of the world, and meets many people who guide him on his quest. But the journey is not as straightforward as it seems at first. Coelho reminds us: “Making a decision was only the beginning of things. When someone makes a decision, he is really diving into a strong current that will carry him to places he has never dreamed of when he first made the decision” (p. 70).

Why It’s Worth Reading

The Alchemist helps us remember that everyone has his or her own journey. Sometimes these journeys intersect. Sometimes they may be different from our own.

This makes me think about every learner that I interact with. My journey may be to forge students’ independence in reading, and to empower them to achieve writerly voices. But their journeys may be different. I just have to appreciate the time in which we have intersected on our journeys.

As Santiago learns about another, “Everyone has his or her own way of learning things. His way isn’t the same as mine, nor mine as his. But we’re both in search of our personal legends, and I respect him for that” (p. 86).

Beyond this important theme, The Alchemist resonates because it’s a joyful read, and its language is beautiful. The ideas are structured like those in a fable, too. This allows every reader to gain meaning from Santiago’s experiences.

I mirror Macklemore when I say, read The Alchemist. I hope you realize that it is a book from which you can find meaning at any point in your life. I daresay that, with multiple readings, you may find a different journey for yourself. And it is a great text for students who are in transitions–including those transitioning between middle and high school, and high school and college.

Book Details:

Reading Level: 910L

ISBN: 978-0062315007

Format: Paperback

Publisher: Harper One

Publication Date: April 15, 2014

Awards and Accolades: Anniversary Edition, New York Times Bestseller

*Thanks to Bethany Bratney for the blog structure for a book recommendation.

Amy Gurney (@agurney_amy) is an ELA and Social Studies Curriculum Coordinator for Walled Lake Schools. She has a Master’s degree from Michigan State University in Educational Administration and an Education Specialist in Educational Leadership from Oakland University. She is a Galileo Alumni. She worked on the MAISA units of study and has studied reading and writing workshop practice and conducted action research.

Amy Gurney (@agurney_amy) is an ELA and Social Studies Curriculum Coordinator for Walled Lake Schools. She has a Master’s degree from Michigan State University in Educational Administration and an Education Specialist in Educational Leadership from Oakland University. She is a Galileo Alumni. She worked on the MAISA units of study and has studied reading and writing workshop practice and conducted action research.

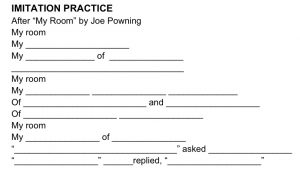

I teach close reading strategies for fiction and informational reading. According to Fisher and Frey,

I teach close reading strategies for fiction and informational reading. According to Fisher and Frey,  I recently had the opportunity to work with a teacher on a unit of study. I went into the experience knowing that I was going to take on the role of an instructional coach, which means I would assist the teacher to improve instruction and outcomes.

I recently had the opportunity to work with a teacher on a unit of study. I went into the experience knowing that I was going to take on the role of an instructional coach, which means I would assist the teacher to improve instruction and outcomes. Many other things play into a strong workshop classroom: classroom culture, student-teacher relationships, grading, feedback, and exemplars, to name a few. In my coaching, I began to model a classroom that ran like my own workshop classroom, with all of these structures in place.

Many other things play into a strong workshop classroom: classroom culture, student-teacher relationships, grading, feedback, and exemplars, to name a few. In my coaching, I began to model a classroom that ran like my own workshop classroom, with all of these structures in place. Writing instruction has become my favorite part of teaching, though it didn’t always come easily. In the beginning, my own writing was stilted in structure and lacked voice. I wrote what I had been taught, which was a five paragraph essay and a five sentence paragraph. Not only was my writing boring. The moves I made to create it were not defined enough for students to use as models, except for stilted, formulaic writing that also lacked voice and a sense of ownership.

Writing instruction has become my favorite part of teaching, though it didn’t always come easily. In the beginning, my own writing was stilted in structure and lacked voice. I wrote what I had been taught, which was a five paragraph essay and a five sentence paragraph. Not only was my writing boring. The moves I made to create it were not defined enough for students to use as models, except for stilted, formulaic writing that also lacked voice and a sense of ownership. Quickly introduced to the intricacies of

Quickly introduced to the intricacies of

I am lucky to have a new job this year as a Curriculum Coordinator for English Language Arts and Social Studies in a new school district. Since I am new to the district, I found myself at New Teacher Orientation. At these sessions, the upper administration focuses on the district’s vision, and how the new teachers are going to be a part of that vision. Having progressed through the ranks with a lot of time in classrooms, administrators tend to share anecdotes about times when they helped to develop this vision, or instances in which they found satisfaction in keeping this vision.

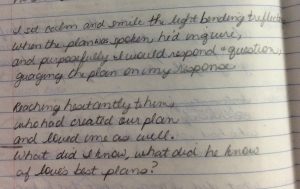

I am lucky to have a new job this year as a Curriculum Coordinator for English Language Arts and Social Studies in a new school district. Since I am new to the district, I found myself at New Teacher Orientation. At these sessions, the upper administration focuses on the district’s vision, and how the new teachers are going to be a part of that vision. Having progressed through the ranks with a lot of time in classrooms, administrators tend to share anecdotes about times when they helped to develop this vision, or instances in which they found satisfaction in keeping this vision. Kids should be given an opportunity to write consistently. This writing should be varied and open to student choice. This choice may be in the strategy they use to produce writing, the length of the writing, the topic of the writing, or even the genre of the writing. Why is this important? Students who write and make choices about writing develop critical thinking skills needed in our world.

Kids should be given an opportunity to write consistently. This writing should be varied and open to student choice. This choice may be in the strategy they use to produce writing, the length of the writing, the topic of the writing, or even the genre of the writing. Why is this important? Students who write and make choices about writing develop critical thinking skills needed in our world. A recent article in the School Library Journal addresses a commonly heard statement in education: “Kids hate to write.”

A recent article in the School Library Journal addresses a commonly heard statement in education: “Kids hate to write.”

At my school, we had a reading goal of 20 books a year for each student. This goal was further broken down into page goals for grade levels — 400 pages each month for 6th graders, 500 for 7th graders, and 600 for 8th graders.

At my school, we had a reading goal of 20 books a year for each student. This goal was further broken down into page goals for grade levels — 400 pages each month for 6th graders, 500 for 7th graders, and 600 for 8th graders. As we continued, for many it was easy to double the two-week goal. For others who struggled to meet their goals, the common theme was that they didn’t make time to read daily. So we used a daily reading log, a visual tool that allowed students to see their amount of reading.

As we continued, for many it was easy to double the two-week goal. For others who struggled to meet their goals, the common theme was that they didn’t make time to read daily. So we used a daily reading log, a visual tool that allowed students to see their amount of reading. As a workshop-model Language Arts teacher, I am always searching for excellent mentor texts to guide students’ writing and reading. The hardest mentor texts to find are informational texts that are grade-level appropriate, as well as high interest in content.

As a workshop-model Language Arts teacher, I am always searching for excellent mentor texts to guide students’ writing and reading. The hardest mentor texts to find are informational texts that are grade-level appropriate, as well as high interest in content.