The other day, my eight year old was brimming with questions about the Revolutionary War. As I went through each, I found myself using vocabulary that he needed me to explain, like alliance–after which he quickly said, “Oh, I get it! My buddy is my alliance on the playground.”

The other day, my eight year old was brimming with questions about the Revolutionary War. As I went through each, I found myself using vocabulary that he needed me to explain, like alliance–after which he quickly said, “Oh, I get it! My buddy is my alliance on the playground.”

My son is lucky that I majored in history in college. Yet, as teachers, we need to recognize that many of our kids do not have these experiences when they’re young. This opportunity gap explains why some students arrive to high school prepared to grapple with text complexity, while others continually struggle.

The Common Core State Standards state that ninth graders must be able to “[c]ite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text” (CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.9-10.1). This ability to infer depends greatly on the student’s prior knowledge.

So how do we play ten years of catch-up in four years of high school?

Teach Kids to be Resourceful

As an academic interventionist, I’ve learned that many students who struggle to understand the course content are also struggling to read the textbook.

Many students simply read the text without paying any mind to the accompanying images, graphs, charts, and summary boxes. In Text and Lessons for Content Area Reading, by Harvey “Smokey” Daniels and Nancy Steineke, the authors explain that reading is easier when “the text makes ample use of pictures, charts, and other visual and text features that support and add meaning.”

When I work with underperforming students, I first show them how to use these features. I show them how to preview the text, by modeling an image walk, observing headings and bolded words, and reading the end-of-the-chapter summary before actually beginning the reading. This helps build context for students who may be unfamiliar with the content.

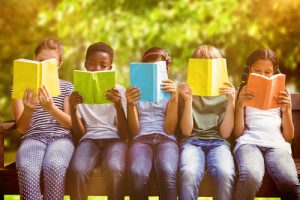

Create a Collaborative Culture

Context in any subject area often begins informally through conversation. Creating a classroom based on discussion, then, effectively engages struggling learners by giving them an entry point. When I taught English 9, I incorporated frequent, low-stakes discussion opportunities. When students discuss content, they make their thinking visible, and teachers see what gaps need to be filled.

Early on in the school year, I introduced my students to the “think-pair-share” protocol. My students could anticipate and prepare to verbally discuss ideas, and soon this routine was normalized.

Some teachers may feel hesitant to put an underperforming reader on the spot, but there are ways to scaffold discussion:

- I often had students spend a few moments writing down their ideas on paper before sharing with a partner.

- I arranged my room in either pairs or quads, so that turning and talking was natural.

- My students also needed processing time, in which they could ask questions and grapple with the content.

Authentic context is built upon multiple sources–not merely upon the teacher quickly rattling through facts. Having this time to discuss with peers and think aloud was important for resistant readers.

Model Strategic Reading

This year, I have worked closely with U.S. History students to engage with the content. Many of them tell me things like, “I can read this, but I don’t get it” or “I just can’t pay attention.”

I began to notice a difference in how my students were performing on tests when I taught them how to text code. This strategy, also from Daniels and Steineke, instructs students to label details of the text with symbols, engaging in an abbreviated reader response. Daniels and Steineke offer a general list of text codes that students can use to monitor comprehension, and I adapted this strategy to text code for content-specific details.

I worked with U.S. History students studying America’s entry into the first World War, for instance, and helped them develop the text codes (N and DW) shown here:

As students went through the text, they used these codes, and categorized the actions leading up to the U.S. entry into WWI.

Text coding provides students with a framework, which is especially important for those who lack prior knowledge. It also serves as a scaffold to show students which details matter, helping them to pay better attention to the text and prepare them to annotate independently.

Moving Forward

Teachers can’t turn back time. But they can establish routines and norms that create growth for underperforming readers.

There is not a one-size-fits-all solution for students who lack contextual knowledge. Still, by teaching students to read strategically and collaboratively with others, we include–rather than exclude–developing readers in the secondary classroom.

Lauren Nizol (@CoachNizol) is an MTSS Student Support Coach and Interventionist at Novi High School. She has eleven years of classroom experience, teaching English, IB Theory of Knowledge and English Lab. Lauren completed her undergraduate degree in History, English and Secondary Education at the University of Michigan-Dearborn and her Masters in English Education from Eastern Michigan University. She is a National Writing Project Teacher Consultant with the Eastern Michigan Writing Project and an advocate for underperforming students and literacy interventions.

Lauren Nizol (@CoachNizol) is an MTSS Student Support Coach and Interventionist at Novi High School. She has eleven years of classroom experience, teaching English, IB Theory of Knowledge and English Lab. Lauren completed her undergraduate degree in History, English and Secondary Education at the University of Michigan-Dearborn and her Masters in English Education from Eastern Michigan University. She is a National Writing Project Teacher Consultant with the Eastern Michigan Writing Project and an advocate for underperforming students and literacy interventions.

Lauren Nizol (@CoachNizol) is an MTSS Student Support Coach and Interventionist at Novi High School. She has eleven years of classroom experience, teaching English, IB Theory of Knowledge and English Lab. Lauren completed her undergraduate degree in History, English and Secondary Education at the University of Michigan-Dearborn and her Masters in English Education from Eastern Michigan University. She is a National Writing Project Teacher Consultant with the Eastern Michigan Writing Project and an advocate for underperforming students and literacy interventions. When she’s not teaching, Lauren often runs for the woods with her husband and their three sons/Jedi in training and posts many stylized pictures of trees on Instagram.

Lauren Nizol (@CoachNizol) is an MTSS Student Support Coach and Interventionist at Novi High School. She has eleven years of classroom experience, teaching English, IB Theory of Knowledge and English Lab. Lauren completed her undergraduate degree in History, English and Secondary Education at the University of Michigan-Dearborn and her Masters in English Education from Eastern Michigan University. She is a National Writing Project Teacher Consultant with the Eastern Michigan Writing Project and an advocate for underperforming students and literacy interventions. When she’s not teaching, Lauren often runs for the woods with her husband and their three sons/Jedi in training and posts many stylized pictures of trees on Instagram.

These are some of the comments I’ve heard over the years from boy readers. But, for every boy who makes remarks like these, there is a book that will save reading.

These are some of the comments I’ve heard over the years from boy readers. But, for every boy who makes remarks like these, there is a book that will save reading.

With the holidays coming, teaching curriculum in any cohesive fashion can be challenging–at best.

With the holidays coming, teaching curriculum in any cohesive fashion can be challenging–at best.  I’m not even finished reading

I’m not even finished reading  The Hate U Give

The Hate U Give Regulars on this blog are probably betting all the money in their bank accounts that I’m going to suggest a graphic novel (just kidding–what teacher has money saved up in a bank account?!). I’m going to branch out in a new direction, though, and recommend a tough but beautiful read by Jesmyn Ward called

Regulars on this blog are probably betting all the money in their bank accounts that I’m going to suggest a graphic novel (just kidding–what teacher has money saved up in a bank account?!). I’m going to branch out in a new direction, though, and recommend a tough but beautiful read by Jesmyn Ward called  About 17 percent of new teachers will leave the profession in their first five years,

About 17 percent of new teachers will leave the profession in their first five years,

The other day, my eight year old was brimming with questions about the Revolutionary War. As I went through each, I found myself using vocabulary that he needed me to explain, like alliance–after which he quickly said, “Oh, I get it! My buddy is my alliance on the playground.”

The other day, my eight year old was brimming with questions about the Revolutionary War. As I went through each, I found myself using vocabulary that he needed me to explain, like alliance–after which he quickly said, “Oh, I get it! My buddy is my alliance on the playground.”

Lauren Nizol (

Lauren Nizol ( Strong words, right? Whenever I see the words hate and reading this close together, my skin crawls.

Strong words, right? Whenever I see the words hate and reading this close together, my skin crawls.