Next month I hope to bring you an update from my graphic novel project (yes, it has officially become a project!), but in the meantime, I thought I might talk for a bit about the great characters of literature . . . and Star Wars. Half kidding.

Next month I hope to bring you an update from my graphic novel project (yes, it has officially become a project!), but in the meantime, I thought I might talk for a bit about the great characters of literature . . . and Star Wars. Half kidding.

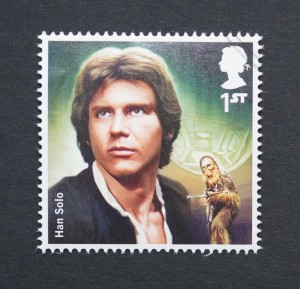

I read a fantastic article at Slate that argued that Han Solo, the reckless heartthrob who melted hearts across the galaxy, was actually a doofus. It’s a wonderfully fun read, and I highly recommend it.

But the piece is also useful for your classroom. Most notably, it’s a real-world, colorful version of a paper I’m almost certain your kids are writing: the character analysis essay. It’s a chore we’ve tasked students with for decades, and with good reason. But be honest—have you ever handed them a published version of that same classroom staple? Here’s one in living color—and timely and relevant to their pop-culture interests to boot.

Characters—They’re Just Like Us! (Complicated!)

Equally interesting are the article’s assertions about a popular figure. I’m not sure I buy all of the writer’s arguments. But note how effectively she supports every assertion with dialogue and other evidence right from the text (in this case a film). It’s like she’s writing a model analysis paper or informative essay. Imagine that—our classroom skills at work in the real world, being read by tens of thousands. And for pleasure, no less!

But here’s what is really worth noting. The piece recognizes something that I don’t think we help kids to wrestle with enough: the inherent complexity of a well written character.

Challenging a Challenging Text

My students just finished The Crucible, and their fury at Abigail for the unjust hanging of 19 innocent people is still burning at their insides. As well it should be. But I posed a question to them that they largely rejected: Isn’t Abby sympathetic in some ways?

John Proctor had an affair with her, even though she’s an innocent teenage girl, in a society where such people are already powerless. Proctor is largely portrayed as the hero of the play, but his sins (which he does admit) are perhaps worse than even he is prepared to acknowledge.

I think we might improve our students’ analytical abilities if we helped them to recognize something: the binary protagonist-antagonist structure, which they learned so long ago, is almost non-existent in actual literature—or film, or any other storytelling medium.

Granted, students should be analyzing all sorts of things beyond literature. But this false dichotomy tends to be a trap we fall into every time we read a work of fiction. We embrace questions like “Was Gatsby really great?” or “Were Romeo and Juliet’s deaths inevitable because of their families’ ongoing feud?”

The problem here is that the first question invites a watered-down perception of Gatsby—it can have  no right answer, because he isn’t reducible to that single, misleading adjective in the book’s title. He’s a bootlegger and rather shallow in his desires, but he’s also a man of enormous will and work ethic and, of course, hope. And the second question excuses Romeo and Juliet entirely. What we perhaps should ask about them is whether they might both have survived if either of them had been mature enough to have patience. Their love was noble and beautiful, but my goodness, if I simply HAD to have everything in my life the way I wanted it to be for all eternity within a fortnight, I might wind up dead in a church basement too.

no right answer, because he isn’t reducible to that single, misleading adjective in the book’s title. He’s a bootlegger and rather shallow in his desires, but he’s also a man of enormous will and work ethic and, of course, hope. And the second question excuses Romeo and Juliet entirely. What we perhaps should ask about them is whether they might both have survived if either of them had been mature enough to have patience. Their love was noble and beautiful, but my goodness, if I simply HAD to have everything in my life the way I wanted it to be for all eternity within a fortnight, I might wind up dead in a church basement too.

Overcoming Emotions

Recognizing a character’s complexity is a wonderful starting point for encouraging our students to practice a more important skill. That is, recognizing the inherent complexity of, well, everything. Wouldn’t they be better in almost every subject area if they recognized that a simple, reductive perspective about most subjects is insufficient for understanding it completely?

The idea feels obvious to us as adults, but the acts of reasoning and analytical thinking require a lot of practice—mostly in the area of overcoming our more immediate emotional or intuitive reactions to things. That’s where most of our students are—the phase of existence wherein everything is judged via the first emotion it evokes. Abigail never has a chance. Hamlet is annoying for his indecisiveness. And Han Solo is . . . old. Ew.

With practice, we can help them learn to interpret literature and life more thoroughly. But first we have to identify it as a skill to be practiced and mastered.

Michael Ziegler (@ZigThinks) is a Content Area Leader and teacher at Novi High School. This is his 15th year in the classroom. He teaches 11th Grade English and IB Theory of Knowledge. He also coaches JV Girls Soccer and has spent time as a Creative Writing Club sponsor, Poetry Slam team coach, AdvancEd Chair, and Boys JV Soccer Coach. He did his undergraduate work at the University of Michigan, majoring in English, and earned his Masters in Administration from Michigan State University.

We hear it all the time: ELA is frustrating and maybe an easier subject, because “there’s no right answer.” It’s all argument and evidence. Math and science, on the other hand . . . they’re objective. Who can argue 2+2, or that the sun is 93 million miles away?

We hear it all the time: ELA is frustrating and maybe an easier subject, because “there’s no right answer.” It’s all argument and evidence. Math and science, on the other hand . . . they’re objective. Who can argue 2+2, or that the sun is 93 million miles away? My colleagues and I have been using

My colleagues and I have been using  Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a  In a burst of unexplained energy (see my last

In a burst of unexplained energy (see my last

REGISTER –

REGISTER –